|

by Michael Wagstaff

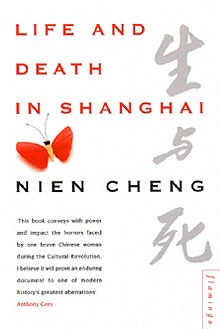

Most of us have learnt much of what we know about post-war China because of Wild Swans, the bestselling memoir of Jung Chang. But Nien Cheng, who died last year in the United States at the age of 94, deserves a wider audience because Life and Death in Shanghai, which centres on her treatment during the Cultural Revolution from 1966-1976, is a terrific read full of insights that are still relevant today 24 years after it was first published in 1986. (Nien Cheng's book was also, incidentally, a hit, occupying a place in the New York Times’s bestseller list for three months.)

Most of us have learnt much of what we know about post-war China because of Wild Swans, the bestselling memoir of Jung Chang. But Nien Cheng, who died last year in the United States at the age of 94, deserves a wider audience because Life and Death in Shanghai, which centres on her treatment during the Cultural Revolution from 1966-1976, is a terrific read full of insights that are still relevant today 24 years after it was first published in 1986. (Nien Cheng's book was also, incidentally, a hit, occupying a place in the New York Times’s bestseller list for three months.)

The most remarkable thing about Life and Death in Shanghai, as the playwright Arthur Miller commented when it first came out, is how well it is written; in a careful, lucid, almost Jamesian way, that totally matches the personality of this upper-class, self-assured woman. But whereas Henry James devoted himself, in the main, to drawing-room manoeuvres, Nien Cheng maintained the same control while she was holed up in Detention Centre No 1 for six and a half years, for most of the time in solitary confinement, suffering intense cold in the winter and almost dying from the punitive treatment that was dished out by radicals who were trying to make her 'confess'. It is a testament to the power of the book that the account of her interrogations includes passages that made me laugh out loud as she runs rings around her persecutors, even drawing wan smiles from some of her Maoist questioners. It is a tribute to her resilience that, at the age of almost 70, she was able to make such a full recovery from her ordeal (which included the death of her daughter Meiping) and could recount these events with such guile and aplomb after she left China and settled down in Washington DC. Nien Cheng was educated in Britain, marrying an official in the Kuomintang government who, after 1949. became the oil company Shell's representative in Shanghai. After her husband died in 1958 she became a senior Shell adviser. All this, of course, counted against her once the Cultural Revolution got going. As far as Nien Cheng is concerned she never broke the law, neither did her colleagues and neither did the firm. End of matter. As far as Nien Cheng is concerned Shell was a benign entity. For Beijing after 1949 Shell, in common with other foreign firms, was a necessary evil, just as it had been for Lenin in the 1920s, a means of obtaining crucial foreign currency. Then the wheel turned and Maoist voluntarism became de rigueur. The radicals, and Chiang Ching, Mao’s wife, in particular wanted to extort a confession of 'acting as a spy' out of Nien Cheng because they wanted to use this as ammunition to discredit Chou En-lai, the prime minister, who had initiated the policy of making links with foreign firms. To the Gang of Four, notably Chiang Ching, Chou En-lai was the leading 'capitalist roader' who had to be removed. Unfortunately for the revolutionaries they met their match in Nien Cheng. No confession was ever forthcoming. She even rubbed salt in the wound by offering a defence of Liu Shao-chi, the General Secretary, after he had been purged. If you wanted to be unkind to Nien Cheng you could say that she was a bit of a cold fish who had led a comfortable and sheltered life until 1967 (Shell, predictably enough, provided her with a first-class jumbo jet ticket to the US when she left China in 1980) and had little understanding of the lot of most Chinese people. And that what sympathy she did show was doled out magnanimously at arm's length via charity rather than solidarity. There is certainly some truth in that portrait and she makes no bones about some of it. But don't be put off: there are many insights and lots of cameos from Chinese life here, Mr Hu, the Chu family, Da Te, the list goes on. One thing is certainly true: she was a formidable woman.

|

|||

|

|