Gender: Male

Country: UK

Signup Date:

14 Aug 2006, 22:44

|

Blog Archive

[ Older

Newer ]

|

|

|

|

16 May 2008

|

The Human Bottleneck (Mark O’Connor)

The Human Bottleneck  Perhaps the most urgent near-term issue for environmentalists is one that few yet talk about. It is what I call "the human bottleneck". Just as the genus homo itself went through a bottleneck when all but one of its species vanished, and just as even that one survivor, homo sapiens, seems to have fallen at one point to less than 10,000 breeding pairs, so all other species on Earth will soon have to pass through a bottleneck as humans pass through what we hope will be a maximum population of about 9 billion, later this century. This will leave so little land and food for other species that many, perhaps most of them, will perish. Note that the narrowest part of the bottleneck for other species will not necessarily come when the human population peaks. At that stage many, or even most humans will still be living in poverty but aspiring to affluence. Hence the squeeze on all other species will actually continue to get worse, and perhaps very much worse, after the human population peaks. The assumption that world population could peak at approximately 9 billion is taken from

http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/worldpopinfo.html For the assumption that much of that population will still be pursuing increased consumption, and thus intensifying rather than relaxing the squeeze on other species, the author relies on his perception of common experience of human nature and of social inequalities. You'll notice that the graph has such a small scale on the X axis (which covers 200,000 years) that one cannot read fine detail from it about values on the Y axis over the next 50 years (which would be speculative in any case) or the last 50. This suits, because the figures would vary according to what measures are used. e.g. it is commonly said that humans now use some 40% of the Earth's primary production (i.e. plant food created from sunlight). But it does not follow that 60% of Earth's surface is freely available for other species, and I presume less than 20% is in virgin state. It also depends whether one includes the oceans. Virtually no part of the ocean surface is not harvested by fishermen, so this might put us as at present intensively harvesting the production of 80% of the planet rather than 40%. Fortunately, as I say, the graph does not permit of reading its values in such fine detail over short periods --which is another way of saying that the overall shape remains the same pretty much regardless of what measure one uses for human domination. Mark O'Connor CMC,

home page: www.australianpoet.com Mark O'Connor is the author of This Tired Brown Land, Duffy and Snelgrove, NSW, 1994. He was Australia's Olympic poet for the year of the olympics in Sydney. He has published many books of poetry, much of it on ecological subjects.

![]() |

Currently

reading

:

This Tired Brown Land

By

Mark O'Connor

|

22:41

-

0 Comments - 0 Kudos

- Add Comment

-

Edit

- Remove

|

|

|

|

15 May 2008

|

How to Build a Human Bomb (Monbiot)

How to Build a Human Bomb Guantanamo Bay is killing people thousands of miles away.

By George Monbiot.

Published in the Guardian 13th May 2008.  When we learnt last week that Abdallah Salih al-Ajmi had blown himself up in Mosul in northern Iraq, the US government presented this as a vindication of its policies. Al-Ajmi was a former inmate of the detention camp at Guantanamo Bay. The Pentagon says that his attack on Iraqi soldiers shows both that it was right to have detained him and that it is dangerous ever to release the camp's prisoners(1). On the contrary, it shows how dangerous it was to put them there in the first place. When we learnt last week that Abdallah Salih al-Ajmi had blown himself up in Mosul in northern Iraq, the US government presented this as a vindication of its policies. Al-Ajmi was a former inmate of the detention camp at Guantanamo Bay. The Pentagon says that his attack on Iraqi soldiers shows both that it was right to have detained him and that it is dangerous ever to release the camp's prisoners(1). On the contrary, it shows how dangerous it was to put them there in the first place.

Al-Ajmi, according to the Pentagon, was one of at least 30 former Guantanamo detainees who have "taken part in anti-coalition militant activities after leaving US detention"(2). Given that the majority of the inmates appear to have been innocent of such crimes before they were detained, that's one hell of a recidivism rate. In reality it turns out that "anti-coalition militant activities" include talking to the media about their captivity in Guantanamo Bay. The Pentagon lists the Tipton Three in its catalogue of recidivists, on the grounds that they collaborated with Michael Winterbottom's film The Road to Guantanamo. But it also names seven former prisoners, aside from Al-Ajmi, who have fought with the Taliban or Chechen rebels, kidnapped foreigners or planted bombs after their release. One of two conclusions can be drawn from this evidence, and neither reflects well on the US government. The first is that, as the Pentagon claims, these men "successfully lied to US officials, sometimes for over three years." (3) The US government's intelligence gathering and questioning were ineffective, and people who would otherwise have been identified as terrorists or resistance fighters were allowed to walk free, despite years of intense and often brutal interrogation. Should this be surprising? Without a presumption of innocence, without charges, representation, trials or due process of any kind, there is no reliable means of determining whether or not a man is guilty. The abuses at Guantanamo Bay not only deny justice to the inmates, they also deny justice to the world. Al-Ajmi, the authorities say, initially confessed in the prison camp to deserting the Kuwaiti army to join the jihad in Afghanistan(4). He admitted that he fought with Taliban forces against the Northern Alliance. He later retracted this confession, which had been made "under pressure and threats"(5). When the Americans released him from Guantanamo, they handed him over to the Kuwaiti government for trial, but without the admissable evidence required to convict him. Among his defences was that neither he nor his interrogators had signed his supposed testimony(6). The Kuwaiti courts, without reliable evidence to the contrary, found him innocent. All evidence obtained in Guantanamo Bay, and in the CIA's other detention centres and secret prisons, is by definition unreliable, because it is extracted with the help of coercion and torture. Torture is notorious for producing false confessions, as people will say anything to make it stop. Both official accounts and the testimonies of former detainees show that a wide range of coercive techniques – devised or approved at the highest levels in Washington - have been used to make inmates tell the questioners what they want to hear. In his book Torture Team, Philippe Sands describes the treatment of Mohammed al-Qahtani, held in Guantanamo Bay and described by the authorities (like half a dozen other suspects) as "the 20th hijacker". By the time his interrogators started using "enhanced techniques" to extract information from him, al-Qahtani had been kept in isolation for three months in a cell permanently flooded with light. An official memo shows that he "was talking to non-existent people, reporting hearing voices, [and] crouching in a corner of the cell covered with a sheet for hours on end."(7) He was sexually abused, exposed to extreme cold and deprived of sleep for a further 54 days of torture and questioning. What useful testimony could be extracted from a man in this state? The other possibility is that the men who became involved in armed conflict after their release had not in fact been involved in any prior fighting, but were radicalised by their detention. In the video he made before blowing himself up, al-Ajmi maintained that he was motivated by his ill-treatment in Guantanamo Bay. "Twelve thousand kilometers away from Mecca, I realized the reality of the Americans and what those infidels want," he said(8). He claimed he was beaten, drugged and "used for experiments" and that "the Americans delighted in insulting our prayer and Islam and they insulted the Koran and threw it in dirty places."(9) Al-Ajmi's lawyer revealed that his arm had been broken by guards at the camp, who beat him up to stop him from praying(10). The accounts of people released from Guantanamo Bay describe treatment that would radicalise almost anyone. In his book Five Years of My Life, published a fortnight ago, Murat Kurnaz maintains that one of the guards greeted him on his arrival with these words. "Do you know what the Germans did to the Jews? That's exactly what we're going to do with you." There were certain similarities. "I knew a man from Morocco," Kurnaz writes, "who used to be a ship captain. He couldn't move one of his little fingers because of frostbite. The rest of his fingers were all right. They told him they would amputate the little finger. They brought him to the doctor, and when he came back, he had no fingers left. They had amputated everything but his thumbs." The young man – scarcely more than a boy - in the cage next to Kurnaz's had just had his legs amputated by American doctors after getting frostbite in a coalition prison in Afghanistan. The stumps were still bleeding and covered in pus. He received no further treatment or new dressings. Every time he tried to hoist himself up to sit on his pot by clinging to the wire, a guard would come and hit his hands with a billy-club. Like every other prisoner, he was routinely beaten by the camp's Immediate Reaction Force, and taken away to interrogation cells to be beaten up some more(11). Fathers were clubbed in front of their sons, sons in front of their fathers. The prisoners were repeatedly forced into stress positions, deprived of sleep and threatened with execution. As a senior official at the US Defense Intelligence Agency says, "maybe the guy who goes into Guantanamo was a farmer who got swept along and did very little. He's going to come out a fully fledged jihadist."(12) In reading the histories of Guantanamo Bay, and of the kidnappings, extrajudicial detention and torture the US government (helped by the United Kingdom) has pursued around the world, two things become clear. The first is that these practices do not supplement effective investigation and prosecution; they replace them. Instead of a process which generates evidence, assesses it and uses it to prosecute, the US has deployed a process which generates nonsense and is incapable of separating the guilty from the innocent. The second is that far from protecting innocent lives, this process is likely to deliver further atrocities. Even if you put the ethics of such treatment to one side, it is surely evident that it makes the world more dangerous. www.monbiot.com References: 1. Josh White, 8th May 2008. Ex-Guantanamo Detainee Joined Iraq Suicide Attack. Washington Post. 2. Department of Defense, 12th July 2007. Former Guantanamo detainees who have returned to the fight. http://www.defenselink.mil/news/d20070712formergtmo.pdf 3. ibid 4. Office for the Administrative Review of the Detention of Enemy Combatants at US Naval Base, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, Department of Defense, No date given. Abdallah Salih Ali Al Ajmi: summary of evidence. Pp8-9 of the pdf file.

http://www.dod.mil/pubs/foi/detainees/csrt_arb/000201-000299.pdf38 5. Department of Defense, no date given. Summarized Administrative Review Board Detainee Statement. Page 47 of the pdf. http://www.dod.mil/pubs/foi/detainees/csrt/ARB_Transcript_Set_17_22822-23051.pdf466. 6. No author given, 26th May 2006. 5 ex-Guantanamo detainees freed in Kuwait. Associated Press. 7. Philippe Sands, 2008. Torture Team: Rumsfeld's Memo and the Betrayal of American Values, extracted in Vanity Fair, May 2008. 8. Quoted by Alissa J. Rubin, 9th May 2008. Bomber's Final Messages Exhort Fighters Against US. New York Times. 9. ibid. 10. Ben Fox, 7th M ay 2008. Ex-Gitmo prisoner in recent attack. Associated Press. 11. Murat Kurnaz, 2008. Five Years of My Life: An Innocent Man in Guantanamo. Palgrave Macmillan. Extracted in the Guardian, 23rd April 2008. 12. Quoted by David Rose, 26th February 2006. Using terror to fight terror. The Observer.

http://www.monbiot.com/archives/2008/05/13/how-to-build-a-human-bomb/

21:34

-

0 Comments - 2 Kudos

- Add Comment

-

Edit

- Remove

|

|

|

Is the world’s food system collapsing? (New Yorker)

The Last Bite

Is the world's food system collapsing?

by Bee Wilson

May 19, 2008

http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/atlarge/2008/05/19/080519crat_atlarge_wilson?printable=true  The global food market fosters both scarcity and overconsumption, while imperilling the planet's ability to produce food in the future. Photograph by James Nachtwey. The global food market fosters both scarcity and overconsumption, while imperilling the planet's ability to produce food in the future. Photograph by James Nachtwey.In his "Essay on the Principle of Population," of 1798, the English parson Thomas Malthus insisted that human populations would always be "checked" (a polite word for mass starvation) by the failure of food supplies to keep pace with population growth. For a long time, it looked as if what Malthus called the "dark tints" of his argument were unduly, even absurdly, pessimistic. As Paul Roberts writes in "The End of Food" (Houghton Mifflin; $26), "Until late in the twentieth century, the modern food system was celebrated as a monument to humanity's greatest triumph. We were producing more food—more grain, more meat, more fruits and vegetables—than ever before, more cheaply than ever before, and with a degree of variety, safety, quality and convenience that preceding generations would have found bewildering." The world seemed to have been liberated from a Malthusian "long night of hunger and drudgery." Now the "dark tints" have returned. The World Bank recently announced that thirty-three countries are confronting food crises, as the prices of various staples have soared. From January to April of this year, the cost of rice on the international market went up a hundred and forty-one per cent. Pakistan has reintroduced ration cards. In Egypt, the Army has started baking bread for the general population. The Haitian Prime Minister was ousted after hunger riots. The current crisis could push another hundred million people deeper into poverty. Is the world's population about to be "checked" by its failure to produce enough food? Paul Roberts is the second author in the past couple of years to publish a book entitled "The End of Food"—the first, by Thomas F. Pawlick, appeared in 2006. Pawlick, an investigative journalist from Ontario, was concerned with such predicaments as the end of the tasty tomato and its replacement by "red tennis balls" lacking in both flavor and nutrients. (The modern tomato, he reported, contains far less calcium and Vitamin A than its 1963 counterpart.) These worries seem rather tame compared with Roberts's; his book grapples with the possible termination of food itself, and its replacement by—what? Cormac McCarthy's novel "The Road" contains a vision of a future in which just about the only food left is canned, from happier times; when the cans run out, the humans eat one another. Roberts lacks McCarthy's Biblical cadences, but his narrative is intended to be no less terrifying. Roberts's work is part of a second wave of food-politics books, which has taken the genre to a new level of apocalyptic foreboding. The first wave was led by Eric Schlosser's "Fast Food Nation" (2001), and focussed on the perils of junk food. "Fast Food Nation" painted an alarming picture—one learned about the additives in a strawberry milkshake, the traces of excrement in hamburger meat—but it also left some readers with a feeling of mild complacency, as they closed the book and turned to a wholesome supper of spinach and ricotta tortellini. There is no such reassurance to be had from the new wave, in which Roberts's book is joined by "Stuffed and Starved: The Hidden Battle for the World Food System," by Raj Patel (Melville House; $19.95); "Bottomfeeder: How to Eat Ethically in a World of Vanishing Seafood," by Taras Grescoe (Bloomsbury; $24.99); and "In Defense of Food: An Eater's Manifesto," by Michael Pollan, the poet of the group (Penguin Press; $21.95). All of these authors agree that the entire system of Western food production is in need of radical change, right down to the spinach. Roberts opens with a description of E.-coli-infected spinach from California, which killed three people in 2006 and sickened two hundred others. The E. coli was traced to the guts of a wild boar that may have tracked the bug in from a nearby cattle ranch. Industrial farming means that even those on a vegan diet may reap the nastier effects of intensive meat production. It is no longer enough for individuals to switch to "healthier" choices in the supermarket. Schlosser asked his readers to consider the chain of consequences they set in motion every time they sit down to eat in a fast-food outlet. Roberts wants us to consider the "chain of transactions and reactions" represented by each of our food purchases—"by each ripe melon or freshly baked bagel, by each box of cereal or tray of boneless skinless chicken breasts." This time, we are all implicated. Like Malthus, Roberts sees humanity increasingly struggling to meet its food needs. He predicts that in the next forty years, as agriculture is threatened by climate change, "demand for food will rise precipitously," outstripping supply. The reasons for this, however, are not strictly Malthusian. For Malthus, famine was inevitable because the math of human existence did not add up: the means of subsistence grew only arithmetically (1, 2, 3), whereas population grew geometrically (2, 4, 8). By this analysis, food production could never catch up with fertility. Malthus was wrong, on both counts. In his treatise, Malthus couldn't envisage any innovations for increasing yield beyond "dressing" the soil with cattle manure. In the decades after he wrote, farmers in England took advantage of new machinery, powerful fertilizers, and higher-yield seeds, and supply rose faster than demand. As the availability of food increased, and people became more prosperous, fertility fell. Malthus could not have imagined that demand might increase catastrophically even where populations were static or falling. The problem is not just the number of mouths to feed; it's the quantity of food that each mouth consumes when there are no natural constraints. As the world becomes richer, people eat too much, and too much of the wrong things—above all, meat. Since it takes on average four pounds of grain to make a single pound of meat, Roberts writes, "meatier diets also geometrically increase overall food demands" even in those parts of Europe and North America where fertility rates are low. Malthus knew that some people were more "frugal" than others, but he hugely underestimated the capacity of ordinary human beings to keep eating. Even now, there is no over-all food shortage when measured by global subsistence needs. Despite the current food crisis, last year's worldwide grain harvest was colossal, five per cent above the previous year's. We are not yet living on Cormac McCarthy's scorched earth. Yet demand is increasing ever faster. As of 2006, there were eight hundred million people on the planet who were hungry, but they were outnumbered by the billion who were overweight. Our current food predicament resembles a Malthusian scenario—misery and famine—but one largely created by overproduction rather than underproduction. Our ability to produce vastly too many calories for our basic needs has skewed the concept of demand, and generated a wildly dysfunctional market. Michael Pollan writes that the food business once lamented what it called the problem of the "fixed stomach"—it appeared that demand for food, unlike other products, was inelastic, the amount fixed by the dimensions of the stomach itself, the variety constrained by tradition and habit. In the past few decades, however, American and European stomachs have become as elastic as balloons, and, with the newly prosperous Chinese and Indians switching to Western diets, much of the rest of the world is following suit. "Today, Mexicans drink more Coca-Cola than milk," Patel reports. Roberts tells us that in India "obesity is now growing faster than either the government or traditional culture can respond," and the demand for gastric bypasses is soaring. Driven by our bottomless stomachs, Roberts argues, the modern economy has reduced food to a "commodity" like any other, which must be generated in ever greater units at an ever lower cost, year by year, like sneakers or DVDs. But food isn't like sneakers or DVDs. If we max out our credit cards buying Nikes, we can simply push them to the back of a closet. By contrast, our insatiable demand for food must be worn on our bodies, often in the form of diabetes as well as obesity. Overeating makes us miserable, and ill, but medical advances mean that it takes a long time to kill us, so we keep on eating. Roberts, whose impulse to connect everything up is both his strength and his weakness, concludes, grandly, that "food is fundamentally not an economic phenomenon." On the contrary, food has always been an economic phenomenon, but in its current form it is one struggling to meet our uncurbed appetites. What we are witnessing is not the end of food but a market on the brink of failure. Those bearing the brunt are, as in Malthus's day, the people at the bottom. Cheap food, in these books, is the enemy. Roberts complains that "the attributes of food that our economic system tends to value and to encourage"—like cheapness—"aren't necessarily the attributes that work best for the people eating the food, or the culture in which that food is consumed, or the environment in which it is produced." Cheap food distresses Raj Patel, too. Patel, a former U.N. consultant and a current anti-globalization activist, is an excitable fan of peasant coöperatives and Slow Food. He lacks Roberts's cool scope but shares his ambition to connect all the dots. Patel would like us to take lessons in "culinary sensuousness" from his "dear friend" Marco Flavio Marinucci, a San Francisco-based artist and, apparently, a master of the art of "gastronomical foreplay." Patel regrets that most of us are nothing like dear Mr. Marinucci. We are all too busy being screwed over by the giant corporations to take the time to appreciate "the deeper and subtler pleasures of food." For Patel, it is a short step from Western consumers "engorged and intoxicated" with cheap processed food to Mexican and Indian farmers committing suicide because they can't make a living. The "food industry's pabulum" makes us all cogs in an evil machine. It's easy to see what Roberts and Patel have against cheap food. For one thing, it's often disgusting. Roberts has a powerful passage on industrial chicken, showing how its vile flesh is a direct consequence of its status as economic commodity. In the nineteen-seventies, it took ten weeks to raise a broiler; now it takes forty days in a dark and crowded shed, because farmers are under constant pressure to cut costs and increase productivity. Every cook knows that chicken breast is no longer what it once was—it's now remarkably flabby and yielding. Roberts reveals that poultry experts have a term for this: P.S.E., or "pale, soft, exudative" meat. Today's birds, Roberts shows, are bred to be top-heavy, in order to satisfy consumers' desire for "healthy" white meat at affordable prices. In these Sumo-breasted monsters, a vast volume of lactic acid is released upon death, damaging the proteins—hence the crumbly meat. Poultry firms deal with P.S.E. after the fact, pumping the flaccid breast with salts and phosphates to keep it artificially juicier. What they don't do is try particularly hard to prevent P.S.E. They can't afford to. The average U.S. consumer eats eighty-seven pounds of chicken a year—twice as much as in 1980—but this generates a profit of only two cents per pound for the farmer. So, yes, cheap food can be nasty, not to mention bad for farmers and the environment. Yet it has one great advantage that neither Patel nor Roberts fully grapples with: people can afford to buy it. According to the World Bank, four hundred million fewer people were living in extreme poverty in 2004 than was the case in 1981, in large part owing to the affordability of basic foodstuffs. The current food crises are the result of food being too expensive to buy, rather than too cheap. The rioters of Haiti would kill for a plate of affordable chicken, no matter how pale, soft, and exudative. The battle against cheap food involves harder tradeoffs than Patel and Roberts allow. No one has yet discovered how to raise prices for the overfed rich without squeezing the underfed poor. If Roberts's overarching thesis is simplistic, he is nevertheless right in his scathing analysis of some of the market alternatives. The conventional view against which Roberts is arguing is that the food economy is "more or less self-correcting." When the economy gets out of kilter—through rapidly increased demand or sudden shortages and price rises—the market should provide the solution in the form of new technologies that "push the Malthusian monster back into its box." This is precisely what Malthus is thought to have missed—the capacity of a market economy to turn pressures on supply into innovations that can meet future demands. But endless innovation has now generated a series of demands that are starting to overwhelm the market. Roberts depicts the global food market as a lumbering beast, organized on such a monolithic scale that it cannot adapt to the consequences of its own distortions. In a flexible, responsive market, producers ought to be able to react to a surplus of one thing by switching to making another thing. Industrial agriculture doesn't work like this. Too many years—and, in the West, too many subsidies—are invested in the setup of big single-crop farms to let producers abandon them when the going gets tough. Defenders of industrial agriculture point to its efficiency, but Roberts sees instead a system full to bursting with waste, often literally. American consumers demand huge amounts of cheese and meat. One consequence is the giant "poop lagoons" of Northern California. In traditional forms of mixed agriculture, animal manure is not a waste product but a valuable fertilizer. By contrast, the mainstream food economy is now dominated by monocultures in which crops and animals are kept apart. This system of farming has little use for poop, despite churning it out in ever-increasing volumes. The San Joaquin Valley has air quality as poor as Los Angeles, the result of twenty-seven million tons of manure produced every year by California's cows. "And cows are relatively benign crappers," Roberts points out; hogs—mass-produced to meet the demand for bacon on everything—are more prolific. On June 21, 1995, Roberts tells us, a hog lagoon burst into a river in North Carolina, destroying aquatic life for seventeen miles. Repulsed by the sordid details of meat production, some consumers turn to fish instead. Yet the piscine world is subject to the same market paradoxes as meat. In "Bottomfeeder," Taras Grescoe confirms that there are still plenty of fish in the sea. Unfortunately, these are not the ones that people want to eat. Aside from pollution, the oceans would be in quite a healthy state if consumers were less reluctant to eat fish near the middle or bottom of the food chain, such as herring, sardines, and mackerel. We would be healthier, too, since these oily fish are rich in omega-3, the fatty acid in which the Western diet is markedly deficient. Instead, we clamor to eat top-of-the-food-chain fish such as cod and bluefin tuna, many of whose stocks have collapsed; they will soon disappear from the seas altogether unless demand drops. So far, as with meat, the opposite is happening. With increasing affluence, the Chinese are developing a taste for sushi, which could soon see every last piece of glistening toro disappear. Fish "farming," with its overtones of pastoral care, sounds like a better option, but Grescoe—who has travelled around the world in search of delicious and rare seafood—shows that it can be more damaging still. As with chicken, out-of-control demand for once premium foods has translated into grotesque and unsustainable forms of production. A taste for "popcorn shrimp in the strip malls of America" translates into the cutting down of tropical mangrove forests in Ecuador and the destruction of wild-shrimp stocks in Southeast Asia. Grescoe quotes Duong Van Ni, a hydrologist from Vietnam, where warm-water shrimp farms feed the insatiable Western appetite for all-you-can-eat seafood-shack specials and prawn curries. "Shrimp farming is so damaging to the environment and so polluting to the soil, trees, and water that it will be the last form of agriculture," Ni says. "After it, you can do nothing." Our thirst for cheap salmon is similarly destructive, and the results are as bad for us as they are for the fish. The nutrition expert Marion Nestle warns that you should broil or grill farmed salmon until it is well done and remove the skin, to get rid of much of the toxin-laden grease. As Grescoe remarks, if this is the only safe way to eat this fish, wouldn't it be better to eat something else? The one thing farmed salmon has going for it is that the fish are, as Roberts says, "efficient feed converters": salmon require only a little more than a pound of feed for every pound of weight that they gain. The trouble is that the feed in this case isn't grain but other fish, because salmon are carnivores. Fishermen are granted large quotas to catch fish like sardines and anchovies—which are delicious and could be eaten by humans—only to have them turned into fish meal and oil. Thirty million tons, or a third of the world's wild catch, goes into the manufacture of fish meal and oil, much of which is used to raise farmed salmon. Farming salmon, Grescoe says, is "akin to nourishing tigers and lions with beef and pork," and then butchering them to make ground beef. The farming of herbivorous fish such as carp and tilapia, by contrast, actually increases the net amount of seafood in the world. The great mystery of the world's insatiable appetite for farmed salmon is that it doesn't taste good. Grescoe, a Canadian who was reared on "well-muscled" chinook, gives a lurid description of the farmed variety, with its "herring-bone-pattern flesh, barely held together by creamy, saliva-gooey fat." A flabby farmed-salmon dinner—no matter how much you dress it up with teriyaki or ginger—cannot compare with the pleasures of canned sardines spread on hot buttered toast or a delicate white-pollock fillet, spritzed with lemon. Pollock is cheaper than salmon, too. Yet in the United States there is little demand for it, or, indeed, for the small, wild, affordable (and sustainable) Northern shrimp, which taste sweeter than the watery jumbo creatures that the market prefers. Given that the current food economy is so strongly driven by appetite, it does seem odd that so much of the desire is for such squalid and unsatisfying things. If we are going to squander the world's resources, shouldn't it at least be for the sake of rare and splendid edibles? Yet much of what is now eaten in the West is not food so much as, in Michael Pollan's terms, stuff that's merely "foodish." From the nineteen-eighties onward, many traditional foods were removed from the shelves and in their place came packages of quasi-edible substances whose selling point was nutritional properties (No cholesterol! Vitamin enriched!) rather than taste. Pollan writes:

There are in fact hundreds of foodish products in the supermarket that your ancestors simply wouldn't recognize as food: breakfast cereal bars transected by bright white veins representing, but in reality having nothing to do with, milk; "protein waters" and "nondairy creamer"; cheeselike foodstuffs equally innocent of any bovine contribution; cakelike cylinders (with creamlike fillings) called Twinkies that never grow stale.

Pollan shows that much of the apparent abundance of choice available to the affluent Western consumer is an illusion. You may spend hours in the supermarket, keenly scrutinizing the labels, but, when it comes down to it, most of what you eat is derived from the high-yield, low-maintenance crops that the food industry prefers to grow, and sells to you in myriad foodish forms. "You may not think you eat a lot of corn and soybeans," Pollan writes, "but you do: 75 percent of the vegetable oils in your diet come from soy (representing 20 percent of your daily calories) and more than half of the sweeteners you consume come from corn (representing around 10 percent of daily calories)." You may never consciously allow soy to pass your lips. You shun soy milk and despise tofu. Yet soy will get you in the end, whether as soy-oil mayo and soy-oil fries; ice cream and chocolate emulsified with soy; or chicken fed on soy ("soy with feathers," as one activist described it to Patel). Our insatiable appetites are not simply our own; they have, in no small part, been created for us. This explains, to a certain degree, how the world can be "stuffed and starved" at the same time, as Patel has it. The food economy has created a system in which some have no food options at all and some have too many options, albeit of a somewhat spurious kind. In the middle is a bottleneck—a relatively small number of wholesalers and buyers who largely determine what the starving farmers produce and what the stuffed consumers eat. In the Netherlands, Germany, France, Austria, Belgium, and the United Kingdom, there are a hundred and sixty million consumers, fed by approximately 3.2 million farmers. But the farmers and the consumers are connected to one another by a mere hundred and ten wholesale "buying desks." It would be futile, therefore, to look to the food system for radical change. The global manufacturers and wholesalers have an interest in continuing to manipulate our desires, feeding our illusions of choice, stoking our colossal hunger. On the other hand, if desires can be manipulated in one direction, why shouldn't they be manipulated in another, more benign direction? Pollan offers a model of how individual consumers might adjust their appetites: "Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants." As a solution, this is charmingly modest, but it is unlikely to be enough to meet the urgency of the situation. How do you get the whole of America—the whole of the world—to eat more like Michael Pollan? The good news is that one developing country has, in the past two decades, conducted a national experiment in a more sustainable food system, proving that it is possible to feed a population less destructively. Farmers gave up synthetic fertilizers and pesticides and replaced them with old-fashioned crop rotations and mixed livestock-crop operations. Big industrial farms were split into smaller coöperatives. The bad news is that the country is Cuba, which was forced to make the switch after the fall of the Soviet Union left it without supplies of agrochemicals. Cuba's experiment depended on its authoritarian state, which commanded the "reallocation" of labor from cities to farms. Even on Cuba's own terms, the experiment hasn't been perfect. On May Day, Raúl Castro announced further radical changes to the farm system in order to reduce reliance on imports. Paul Roberts notes that there is no chance that Americans and Europeans will voluntarily adopt a Cuban model of food production. (You don't say.) He adds, however, that "the real question is no longer what a rich country would do voluntarily but what it might do if its other options were worse."

21:22

-

0 Comments - 0 Kudos

- Add Comment

-

Edit

- Remove

|

|

|

|

13 May 2008

|

What the IPCC models really say (RealClimate)

What the IPCC models really say

Over the last couple of months there has been much blog-viating about what the models used in the IPCC 4th Assessment Report (AR4) do and do not predict about natural variability in the presence of a long-term greenhouse gas related trend. Unfortunately, much of the discussion has been based on graphics, energy-balance models and descriptions of what the forced component is, rather than the full ensemble from the coupled models. That has lead to some rather excitable but ill-informed buzz about very short time scale tendencies. We have already discussed how short term analysis of the data can be misleading, and we have previously commented on the use of the uncertainty in the ensemble mean being confused with the envelope of possible trajectories (here). The actual model outputs have been available for a long time, and it is somewhat surprising that no-one has looked specifically at it given the attention the subject has garnered. So in this post we will examine directly what the individual model simulations actually show.

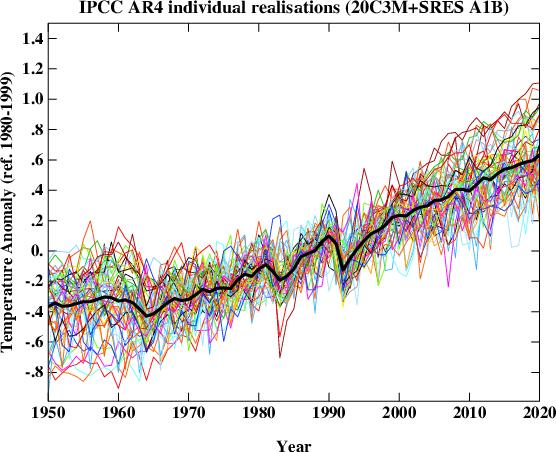

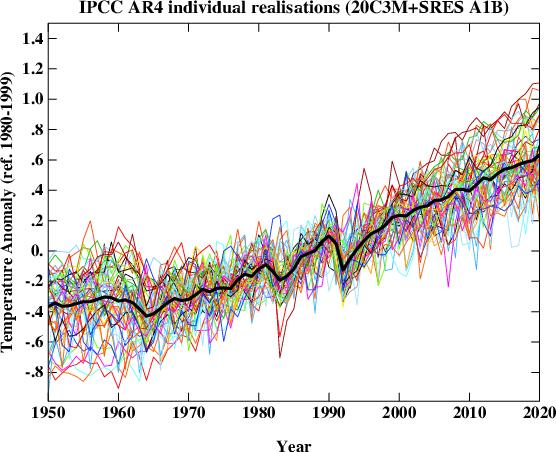

First, what does the spread of simulations look like? The following figure plots the global mean temperature anomaly for 55 individual realizations of the 20th Century and their continuation for the 21st Century following the SRES A1B scenario. For our purposes this scenario is close enough to the actual forcings over recent years for it to be a valid approximation to the simulations up to the present and probable future. The equal weighted ensemble mean is plotted on top. This isn't quite what IPCC plots (since they average over single model ensembles before averaging across models) but in this case the difference is minor.

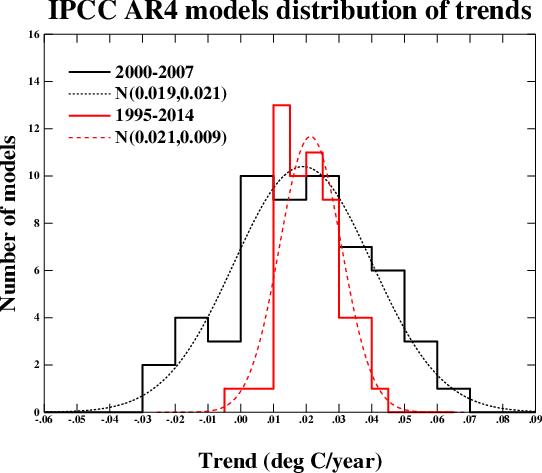

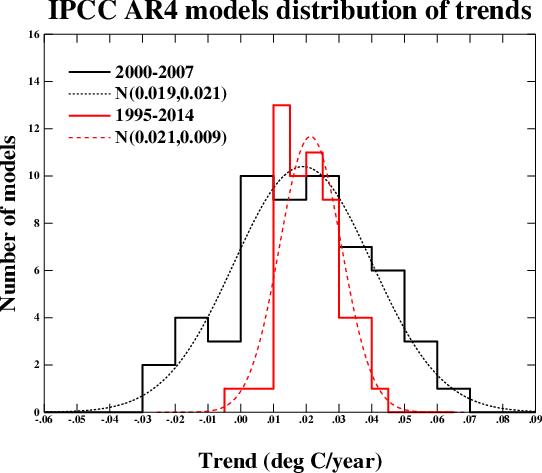

It should be clear from the above the plot that the long term trend (the global warming signal) is robust, but it is equally obvious that the short term behaviour of any individual realisation is not. This is the impact of the uncorrelated stochastic variability (weather!) in the models that is associated with interannual and interdecadal modes in the models - these can be associated with tropical Pacific variability or fluctuations in the ocean circulation for instance. Different models have different magnitudes of this variability that spans what can be inferred from the observations and in a more sophisticated analysis you would want to adjust for that. For this post however, it suffices to just use them 'as is'. We can characterise the variability very easily by looking at the range of regressions (linear least squares) over various time segments and plotting the distribution. This figure shows the results for the period 2000 to 2007 and for 1995 to 2014 (inclusive) along with a Gaussian fit to the distributions. These two periods were chosen since they correspond with some previous analyses. The mean trend (and mode) in both cases is around 0.2ºC/decade (as has been widely discussed) and there is no significant difference between the trends over the two periods. There is of course a big difference in the standard deviation - which depends strongly on the length of the segment.

Over the short 8 year period, the regressions range from -0.23ºC/..o 0.61ºC/dec. Note that this is over a period with no volcanoes, and so the variation is predominantly internal (some models have solar cycle variability included which will make a small difference). The model with the largest trend has a range of -0.21 to 0.61ºC/dec in 4 different realisations, confirming the role of internal variability. 9 simulations out of 55 have negative trends over the period. Over the longer period, the distribution becomes tighter, and the range is reduced to -0.04 to 0.42ºC/dec. Note that even for a 20 year period, there is one realisation that has a negative trend. For that model, the 5 different realisations give a range of trends of -0.04 to 0.19ºC/dec. Therefore: - Claims that GCMs project monotonic rises in temperature with increasing greenhouse gases are not valid. Natural variability does not disappear because there is a long term trend. The ensemble mean is monotonically increasing in the absence of large volcanoes, but this is the forced component of climate change, not a single realisation or anything that could happen in the real world.

- Claims that a negative observed trend over the last 8 years would be inconsistent with the models cannot be supported. Similar claims that the IPCC projection of about 0.2ºC/dec over the next few decades would be falsified with such an observation are equally bogus.

- Over a twenty year period, you would be on stronger ground in arguing that a negative trend would be outside the 95% confidence limits of the expected trend (the one model run in the above ensemble suggests that would only happen ~2% of the time).

A related question that comes up is how often we should expect a global mean temperature record to be broken. This too is a function of the natural variability (the smaller it is, the sooner you expect a new record). We can examine the individual model runs to look at the distribution. There is one wrinkle here though which relates to the uncertainty in the observations. For instance, while the GISTEMP series has 2005 being slightly warmer than 1998, that is not the case in the HadCRU data. So what we are really interested in is the waiting time to the next unambiguous record i.e. a record that is at least 0.1ºC warmer than the previous one (so that it would be clear in all observational datasets. That is obviously going to take a longer time. This figure shows the cumulative distribution of waiting times for new records in the models starting from 1990 and going to 2030. The curves should be read as the percentage of new records that you would see if you waited X years. The two curves are for a new record of any size (black) and for an unambiguous record (> 0.1ºC above the previous, red). The main result is that 95% of the time, a new record will be seen within 8 years, but that for an unambiguous record, you need to wait for 18 years to have a similar confidence. As I mentioned above, this result is dependent on the magnitude of natural variability which varies over the different models. Thus the real world expectation would not be exactly what is seen here, but this is probably reasonably indicative.

We can also look at how the Keenlyside et al results compare to the natural variability in the standard (un-initiallised) simulations. In their experiments, the decadal mean of the period 2001-2010 and 2006-2015 are cooler than 1995-2004 (using the closest approximation to their results with only annual data). In the IPCC runs, this only happens in one simulation, and then only for the first decadal mean, not the second. This implies that there may be more going on than just the tapping into the internal variability in their model. We can specifically look at the same model in the un-initiallised runs. There, the differences between first decadal means spans the range 0.09 to 0.19ºC - significantly above zero. For the second period, the range is 0.16 to 0.32 ºC. One could speculate that there is actually a cooling that is implicit to their initialisation process itself. It would be instructive to try some similar 'perfect model' experiments (where you try and replicate another model run rather than the real world) to investigate this further though. Finally, I would just like to emphasize that for many of these examples, claims have circulated about the spectrum of the IPCC model responses without anyone actually looking at what those responses are. Given that the archive of these models exists and is publicly available, there is no longer any excuse for this. Therefore, if you want to make a claim about the IPCC model results, download them first! Much thanks to Sonya Miller for producing these means from the IPCC archive. Update: Since some people have asked, the test for consistency (at 95% confidence) between the ranges seen in the models in figure 2 and real world trends is that the difference in means must be less than the twice the pooled standard deviation (and since the pooled s.d. is always larger than the s.d. in the models alone, it is trivially true that if the observed mean trend is within the 95% range of the models, it is consistent). See Lanzante 2005 for more info. All observational global SAT trends pass that test. Under no reasonable circumstances is an 8 year trend of -10 deg C/decade (that is 48 s.d. away from the mean) or even -1 deg C/decade going to be consistent with the models. For 7 year trends (beginning of 2001 to end of 2007), the model spread is approximately N(0.2,0.24) in deg C/dec - a little wider than the 8 year trends seen in the figure and there are 10 model simulations with negative trends.

21:28

-

0 Comments - 0 Kudos

- Add Comment

-

Edit

- Remove

|

|

|

The Morality of the Stomach - Food Riots are Coming to the U.S. (CounterPunch)

The Morality of the Stomach Food Riots are Coming to the U.S. By BINOY KAMPMARK

http://www.counterpunch.org/kampmark05082008.html "I don't want to alarm anybody, but maybe it's time for Americans to start stockpiling food. No this is not a drill." --Brett Arends There is a time for food, and a time for ethical appraisals. This was the case even before Bertolt Brecht gave life to that expression in Die Driegroschen Oper. The time for a reasoned, coherent understanding for the growing food crisis is not just overdue, but seemingly past. Robert Zoellick of the World Bank, an organization often dedicated to flouting, rather than achieving its claimed goal of poverty reduction, stated the problem in Davos in January this year. 'Hunger and malnutrition are the forgotten Millennium Development Goal.' Global food prices have gone through the roof, terrifying the 3 billion or so people who live off less than $2 a day. This should terrify everybody else. In November, the UN Food and Agricultural Organization reported that food prices had suffered a 18 percent inflation in China, 13 percent in Indonesia and Pakistan, and 10 percent or more in Latin America, Russia and India. The devil in the detail is even more distressing: a doubling in the price of wheat, a twenty percent increase in the price of rice, an increase by half in maize prices. Finger pointing is not always instructive. In this case, it may be. The US and various European countries are moving food crops into the bio-fuel business, itself an environmentally unsound business. This, in addition to encouraging developing countries to not merely 'liberalize' their agricultural sectors, but specialize in exporting specific cash crops (cotton, cocoa), has done wonders to precipitate the shortages. Consumption in developing economies, added to the vicissitudes of climate change, water availability, and rising fertilizer costs, are others. Political stability is being undermined. Food shortages are proving endemic. Food riots are becoming common. Riots have been sparked in Cameroon, Egypt, Burkina Faso, Uzbekistan and Yemen. There have been riots over spiraling grain prices in Mauritania and Senegal. In Mexico City, mass protests were sparked by a price hike in tortillas. In Haiti, biscuits are being made from a mud compound. The Somali capital Mogadishu bore witness to the deaths of five people. Governments, indifferent and incautious to the demands of a hungry public, have already fallen victim to the food crisis. Prime Minister Jacques Edouard Alexis was dismissed by a senate vote in Haiti after skirmishes between UN forces and protesters. The UN commander Major General Carlos Alberto Dos Santos Cruz urged calm amidst the carnage. 'It is important for the people to have a peaceful life in Haiti,' he claimed in April 2008. The message then: be peaceful on an empty stomach. The Bush administration, so often in arrears on the relief front, has earmarked some 770 million dollars or so in funds dealing with the problem. There is one glaring hitch: the money would only start flowing in 2009. 'There is definitely a lag time when it comes to assistance,' states the senior manager of the Foreign Aid Reform Project at the Brookings Institute, Noam Unger. More troubling is the critique offered of the crisis by officials within the administration. US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, at the Peace Corps conference held at the end of April, targeted various culprits. The audience barely stirred at some of the explanations: distribution, oil prices, and the 'alternate fuels effort'. They duly woke up when Rice moved on to targeting the export strategies of various countries – India and China foremost amongst them. 'We obviously have to look at places where production seems to be declining and declining to the point that people are actually putting export caps on the amount of food.' The problem, for Rice, is rising food consumption. Improved diets within China and India are bothering free market fundamentalists who insist that export caps stifle trade. According to this rationale, Indians are far better off buying the rice from the global market than eating their own in times of crisis. How silly of them to ensure a domestic supply first before shipping off the rest for the global market. Rice is crying foul at such protectionist deviancy, will 'have a look at it' and take the matter to the World Trade Organization. Members of the American public are not so sure. A narrative of catastrophe is gradually building – stockpile or perish. The Wall Street Journal (April 25) was one of the first to issue the clarion call: 'Start Hoarding Food Americans!' The paper had various suggestions. Stock up on some products – dried pasta, rice, cereals, canned products. Buy them all in bulk to save. Sit the children down give them a good talking to – no, not about the birds and the bees, but about 'how our generation and the two behind it, screwed their world into a death spiral through greed and predatory capitalism.' Solutions suggested by such economists as Jeffrey Sachs, somewhat patchy yet desperately needed, are forthcoming: allow easier access for sub-Saharan African farmers to fertilizers; reduce the amount of crops going into bio-fuel development; shore-up climate change policies. Sachs, in his work Common Wealth, also advocates the abolition of states in the face of a crowded planet. But it was state regimes besotted by neoliberal economics that brought us here. They can take us back and remedy the damage. Abolishing them would simply absolve their regimes. In the meantime, the US and some countries in the West may have to brace themselves for a starving army guided by the morality of the stomach. The food riots are coming. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, University of Cambridge. He can be reached at: bkampmark@gmail.com

21:12

-

0 Comments - 0 Kudos

- Add Comment

-

Edit

- Remove

|

|

|

New Earth Rising: Hope for a New Global Dream (EarthMeanders)

New Earth Rising: Hope for a New Global Dream Sufficient and workable individual and social solutions exist for the wide range of ecological, economic, social and personal ills facing the biosphere and humanity; and together they could herald in a new era of global ecological sustainability

http://earthmeanders.blogspot.com/ Long predicted Earth crises -- including climate change, water shortages, abject poverty, extreme weather, food shortages, over-population, biological homogenization, energy scarcity, diminished oceans, political instability and endless resource wars -- are unfolding as expected, and are converging into a new global ecological crisis of unprecedented magnitude. The fundamental root cause of this global crisis is that humans are destroying ecosystems necessary for all life.

Humanity has met and surpassed ecological limits. Failure to develop and implement profound personal and social change, adequate to respond to global ecosystems in mid-collapse, will have profound negative consequences for vast numbers of global citizens who are unable to meet basic needs including food, water, housing, education and health care. The task of our and all time is to find and implement sufficient solutions for the wide range of ills facing the biosphere and humanity. Ongoing arguments whether personal virtue or social enlightenment are the best strategies to promote are mute as frankly things are dire and we need lots of both.

Defining, personally embracing, and gaining social acceptance for a new global dream will require huge amounts of both personal and social change. Yet there is much to build upon, for even as the fateful hour of global ecological collapse nears, the Earth is blooming with responses to each of the symptomatic crises. From relocalized economies to community gardens, from having fewer children to better educating those we have, from driving less while living more richly where we find ourselves, by finding meaning in experience, knowledge and truth rather than competitive consumption, by rejecting ancient superstitions for an understanding that the Earth is alive and sacred -- a slowly awakening public is showing where there is knowledge and will there is hope. I see a new Earth rising.

New Earth Rising: Personal Redemption and Social Transformation

A new global dream of a sustainable, just and equitable world; where peace, truth and ecosystems are the foundation of fulfilling, experience rich lives, is emerging. We are witnessing a "New Earth Rising", a new global consciousness built upon profound individual awakening, that understands through science, intuition and direct observation that protection and restoration of ecological systems (with healthy doses of personal redemption and social transformation) is the meaning of life. This bright green Earth ethic needs to be nurtured to allow it to grow and prosper; displacing the corrosive, corrupt and unsustainable ethic of maximizing personal consumption at the expense of shared social values.

While the Earth and humanity will not emerge unscathed from the wide array of global ecological crises, there exist numerous well-known and well-studied personal and social changes that could dramatically increase the probability of humans, civilization, other species and the Earth surviving. In a globalized, interconnected world something as seemingly innocuous as eating, and how we meet other basic human needs, has profound meaning. What has been particularly lacking in addressing global crises is a comprehensive, integrated approach to all these issues; that seeks to develop and implement sufficient solutions.

New Earth Rising's global dream will stress working to protect and restore core ecological reserves globally while planting organic gardens locally, promoting incentives and sanctions to reduce population while personally reducing consumption, demanding urgent cessation of ecocidal and irredeemable industries such as coal and ancient forest logging while refusing to buy all Earth destroying products, urging investment to meet the full range of human needs for all while personally living rich and simple lives full of laughter and happiness, and the embrace of morality that stresses equity, fairness, sustainability and justice by and for all.

I have written extensively here regarding other elements of an ecologically based worldview, from which a fledgling think-tank named the Sustainability Solutions Initiative has emerged. There I preliminarily identify ten critical global ecological policies necessary to avert global ecological catastrophe while achieving global ecological sustainability at http://www.ecoearth.info/ssi/ .

As ecological limits continue to bite, responses of many types are possible. Technology has a place, but placing our full faith in a technological silver bullet is extremely dangerous because continuing advances are not assured, while unintended consequences are. Individuals and by extension society can dig in and prepare to use every last bit of fossil fuel and other non-renewable resources to prop up artificially high populations and living standards, or we can embrace a new dream of returning to the Earth's bounty, rhythms and limits.

The Earth's greatest remaining unknown is whether epidemic human populations will understand change is essential to survive, and begin to power down voluntarily. Personal inattentiveness is in fact a choice to push things to the very limit, completely undermining the biosphere and ensuring there remain few resources or ecosystems to allow any other type of decent life for humans and all species. As you awake to a New Earth Rising and help others to do so, be strong and resist small-minded ridicule and defensiveness. We are not only right, but together we are the Earth's future hope.

All this talk of ecological collapse may seem extreme, nonsense even. I would imagine that to communities in Darfur and the billions living on under $2 a day the apocalypse has arrived now. All it takes is one particularly bad harvest for these people to slip into starvation. Indeed, it is happening now. If we continue as we are the end of being is upon us. While I am saddened I try to not be afraid because positive individual and social change is possible, trends do not mean assured outcomes, and things can be different if we have vision, feel and care.

Real Spirituality

The technical and scientific tools to achieve global ecological sustainability must be informed by a new Earth ethic that is adequate to the times. The spirituality that is most real is found in our personal connection with the natural world and our responsibility toward her. I would suggest polytheistic ritual and worship of Gaia and nature, rejecting myths of ancient monotheistic gods that made the Earth and now sit in judgment of our every action, are a vital part of a New Earth Rising.

Many will continue to believe in ancient superstitions, and that is fine as long as you do not deny ecological fact, make your beliefs ecologically positive, and take responsibility for how your teachings are impacting these crises. Whatever your faith please consider yourselves stewards of the Earth, protect your habitat, be accountable and ethical, as you live up to the morals your god expects. While I still have doubts whether real fundamental change can come from within these structures, I challenge believers in ancient prophets to prove that accountability to an invisible creator is more likely to lead to an assured long-term future than humanity making informed, ecological science based policy decisions.

Whatever you believe, work on the big issues. Reject small easy victories for committing decisively to adequate solutions to the great issues of our day. And regardless if you win or lose, make a difference and do not be afraid to change. The Earth dramatically needs a small cadre of Earth peace-makers willing to do what it takes to save creation -- including partaking in revolution when other options are exhausted, and the need and opportunity arises.

Anyone thinking their life is going to remain unchanged by converging global crises that are fundamentally ecological in nature is delusional. Either you and your loved ones will be destroyed as ecosystems and society collapse, or how you live will be simplified as part of the global solution. It is hard to imagine how someone could be too radical regarding developing and rapidly propagating a new way of living to avert ecological crises destroying creation. Be the change.

posted by Dr. Glen Barry

21:06

-

0 Comments - 0 Kudos

- Add Comment

-

Edit

- Remove

|

|

|

The World at 350 - A Last Chance for Civilization (Bill McKibben)

The World at 350 - A Last Chance for Civilization

By Bill McKibben

http://www.tomdispatch.com/post/174930/bill_mckibben_the_defining_moment_for_climate_change

Even for Americans, constitutionally convinced that there will always be a second act, and a third, and a do-over after that, and, if necessary, a little public repentance and forgiveness and a Brand New Start -- even for us, the world looks a little Terminal right now. It's not just the economy. We've gone through swoons before. It's that gas at $4 a gallon means we're running out, at least of the cheap stuffClub of Rome types who, way back in the 1970s, went on and on about the "limits to growth" suddenly seem… how best to put it, right. that built our sprawling society. It's that when we try to turn corn into gas, it sends the price of a loaf of bread shooting upwards and starts food riots on three continents. It's that everything is so inextricably tied together. It's that, all of a sudden, those grim All of a sudden it isn't morning in America, it's dusk on planet Earth. There's a number -- a new number -- that makes this point most powerfully. It may now be the most important number on Earth: 350. As in parts per million (ppm) of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. A few weeks ago, our foremost climatologist, NASA's Jim Hansen, submitted a paper to Science magazine with several co-authors. The abstract attached to it argued -- and I have never read stronger language in a scientific paper -- "if humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on earth is adapted, paleoclimate evidence and ongoing climate change suggest that CO2 will need to be reduced from its current 385 ppm to at most 350 ppm." Hansen cites six irreversible tipping points -- massive sea level rise and huge changes in rainfall patterns, among them -- that we'll pass if we don't get back down to 350 soon; and the first of them, judging by last summer's insane melt of Arctic ice, may already be behind us. So it's a tough diagnosis. It's like the doctor telling you that your cholesterol is way too high and, if you don't bring it down right away, you're going to have a stroke. So you take the pill, you swear off the cheese, and, if you're lucky, you get back into the safety zone before the coronary. It's like watching the tachometer edge into the red zone and knowing that you need to take your foot off the gas before you hear that clunk up front. In this case, though, it's worse than that because we're not taking the pill and we are stomping on the gas -- hard. Instead of slowing down, we're pouring on the coal, quite literally. Two weeks ago came the news that atmospheric carbon dioxide had jumped 2.4 parts per million last year -- two decades ago, it was going up barely half that fast. And suddenly, the news arrives that the amount of methane, another potent greenhouse gas, accumulating in the atmosphere, has unexpectedly begun to soar as well. Apparently, we've managed to warm the far north enough to start melting huge patches of permafrost and massive quantities of methane trapped beneath it have begun to bubble forth. And don't forget: China is building more power plants; India is pioneering the $2,500 car, and Americans are converting to TVs the size of windshields which suck juice ever faster. Here's the thing. Hansen didn't just say that, if we didn't act, there was trouble coming; or, if we didn't yet know what was best for us, we'd certainly be better off below 350 ppm of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. His phrase was: "…if we wish to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed." A planet with billions of people living near those oh-so-floodable coastlines. A planet with ever more vulnerable forests. (A beetle, encouraged by warmer temperatures, has already managed to kill 10 times more trees than in any previous infestation across the northern reaches of Canada this year. This means far more carbon heading for the atmosphere and apparently dooms Canada's efforts to comply with the Kyoto Protocol, already in doubt because of its decision to start producing oil for the U.S. from Alberta's tar sands.) We're the ones who kicked the warming off; now, the planet is starting to take over the job. Melt all that Arctic ice, for instance, and suddenly the nice white shield that reflected 80% of incoming solar radiation back into space has turned to blue water that absorbs 80% of the sun's heat. Such feedbacks are beyond history, though not in the sense that Francis Fukuyama had in mind. And we have, at best, a few years to short-circuit them -- to reverse course. Here's the Indian scientist and economist Rajendra Pachauri, who accepted the Nobel Prize on behalf of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change last year (and, by the way, got his job when the Bush administration, at the behest of Exxon Mobil, forced out his predecessor): "If there's no action before 2012, that's too late. What we do in the next two to three years will determine our future. This is the defining moment." In the next two or three years, the nations of the world are supposed to be negotiating a successor treaty to the Kyoto Accord. When December 2009 rolls around, heads of state are supposed to converge on Copenhagen to sign a treaty -- a treaty that would go into effect at the last plausible moment to heed the most basic and crucial of limits on atmospheric CO2. If we did everything right, says Hansen, we could see carbon emissions start to fall fairly rapidly and the oceans begin to pull some of that CO2 out of the atmosphere. Before the century was out we might even be on track back to 350. We might stop just short of some of those tipping points, like the Road Runner screeching to a halt at the very edge of the cliff. More likely, though, we're the Coyote -- because "doing everything right" means that political systems around the world would have to take enormous and painful steps right away. It means no more new coal-fired power plants anywhere, and plans to quickly close the ones already in operation. (Coal-fired power plants operating the way they're supposed to are, in global warming terms, as dangerous as nuclear plants melting down.) It means making car factories turn out efficient hybrids next year, just the way we made them turn out tanks in six months at the start of World War II. It means making trains an absolute priority and planes a taboo. It means making every decision wisely because we have so little time and so little money, at least relative to the task at hand. And hardest of all, it means the rich countries of the world sharing resources and technology freely with the poorest ones, so that they can develop dignified lives without burning their cheap coal. That's possible -- we launched a Marshall Plan once, and we could do it again, this time in relation to carbon. But in a month when the President has, once more, urged us to drill in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, that seems unlikely. In a month when the alluring phrase "gas tax holiday" has danced into our vocabulary, it's hard to see (though it was encouraging to see that Clinton's gambit didn't sway many voters). And if it's hard to imagine sacrifice here, imagine China, where people produce a quarter as much carbon apiece as we do. Still, as long as it's not impossible, we've got a duty to try. In fact, it's about the most obvious duty humans have ever faced. A few of us have just launched a new campaign, 350.org. Its only goal is to spread this number around the world in the next 18 months, via art and music and ruckuses of all kinds, in the hope that it will push those post-Kyoto negotiations in the direction of reality. After all, those talks are our last chance; you just can't do this one light bulb at a time. And if this 350.org campaign is a Hail Mary pass, well, sometimes those passes get caught. We do have one thing going for us: This new tool, the Web which, at least, allows you to imagine something like a grassroots global effort. If the Internet was built for anything, it was built for sharing this number, for making people understand that "350" stands for a kind of safety, a kind of possibility, a kind of future. Hansen's words were well-chosen: "a planet similar to that on which civilization developed." People will doubtless survive on a non-350 planet, but those who do will be so preoccupied, coping with the endless unintended consequences of an overheated planet, that civilization may not. Civilization is what grows up in the margins of leisure and security provided by a workable relationship with the natural world. That margin won't exist, at least not for long, this side of 350. That's the limit we face. Bill McKibben is a scholar-in-residence at Middlebury College and co-founder of 350.org. His most recent book is The Bill McKibben Reader.

21:03

-

0 Comments - 0 Kudos

- Add Comment

-

Edit

- Remove

|

|

|

Latin America: the attack on democracy (Pilger @ New Statesman)

Latin America: the attack on democracy John Pilger Published 24 April 2008 John Pilger argues that an unreported war is being waged by the US to restore power to the privileged classes at the expense of the poor  Beyond the sound and fury of its conquest of Iraq and campaign against Iran, the world's dominant power is waging a largely unreported war on another continent - Latin America. Using proxies, Washington aims to restore and reinforce the political control of a privileged group calling itself middle-class, to shift the responsibility for massacres and drug trafficking away from the psychotic regime in Colombia and its mafiosi, and to extinguish hopes raised among Latin America's impoverished majority by the reform governments of Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia. Beyond the sound and fury of its conquest of Iraq and campaign against Iran, the world's dominant power is waging a largely unreported war on another continent - Latin America. Using proxies, Washington aims to restore and reinforce the political control of a privileged group calling itself middle-class, to shift the responsibility for massacres and drug trafficking away from the psychotic regime in Colombia and its mafiosi, and to extinguish hopes raised among Latin America's impoverished majority by the reform governments of Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia.