|

from december 10 2006 blue vol V, #17 |

|

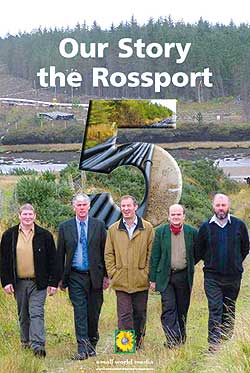

- An Introduction

by Mark Garavan

The courtroom from which they were discharged was packed with their families, supporters, media and politicians. There was barely standing room. When the men emerged into the hall of the Four Courts they were enveloped in an excited crowd of well-wishers. Outside the court, dozens of journalists and cameramen fought to record their initial comments. Large crowds were gathered. The men were accompanied in their walk to the cameras by nearly twenty TDs.

The courtroom from which they were discharged was packed with their families, supporters, media and politicians. There was barely standing room. When the men emerged into the hall of the Four Courts they were enveloped in an excited crowd of well-wishers. Outside the court, dozens of journalists and cameramen fought to record their initial comments. Large crowds were gathered. The men were accompanied in their walk to the cameras by nearly twenty TDs.

The men had entered a different world from that of 94 days previously. Then, the scenes both inside and outside the court were nothing short of horrific. People lay on the footpath overcome with grief and despair. Others stood shocked and numbed that peaceful protest could have resulted in an indefinite prison sentence. When the men entered prison, the Corrib gas project seemed a done deal, certain to go ahead. No one was paying any attention to the demands of locals. Shell had already begun work on excavating peat from the site of their proposed gas processing plant. However, by the time the men were released all of this had changed. The following day the men led a crowd of 5,000 people through the streets of Dublin. That evening, in the early hours of the morning, they returned to Mayo greeted by bonfires and many hundreds of their neighbours. The battle against the Corrib gas project had begun in the autumn of 2000. There were many acts and dramas in the long campaign to get the project re-configured to accommodate local concerns and fears. The release of the men from prison was merely the end of one further scene in this protracted and extraordinary battle between residents in a number of small villages and some of the most powerful oil and gas corporations in the world fully supported by the Irish government. The focus on the men may have obscured the extraordinary events which had unfolded in North Mayo through the summer of 2005. In effect, a local community had revolted and refused to accept a development project that they felt had been imposed on the area. Their refusal was such that irrespective of the law, irrespective of the consequences to themselves, they brought the entire Shell project to a stop. There are thus many books that could be written about the Corrib gas conflict. There is the story of the community revolt, the story of the menís families, particularly their wives, who found themselves carrying much of the burden of the public campaign in their absence, and the story of the other local landowners who had refused consent to Shell such as Monica Muller and Bríd McGarry. This book simply sets out to tell part of the story through the voices of the five men who were imprisoned. It does not purport to offer a comprehensive account of all events nor does it seek to detail the technical objections and analyses that animated the menís opposition. Those matters are for another occasion and a different format. Instead, the attention in this book is on the menís direct experiences at the hands of Shell and the Irish State. What emerges is a tale of resistance to power, of resistance to being treated as objects without a voice. It is tale of a refusal to being exposed to unacceptable levels of risk, a refusal to allow families, community and place be diminished and threatened for the profits of a multi-national corporation. But it is also a tale of the affirmation of community values, of safety, of democracy. Much more was at stake in this conflict than might have been apparent to the casual observer. At issue was the quality of Irish democracy, the integrity of Irish administration, the power and responsibilities of global corporations, environmental well-being and the rights of citizens to dissent and protect themselves from threat. The Corrib gas campaign has brought into vivid relief issues and concerns felt by many in contemporary Ireland and throughout the world. North Mayo has the potential to become Irelandís Chiapas. At the heart of the menís opposition was their profound sense that the insertion of a huge processing plant and associated pipelines into their community, without any participation from themselves and without any long-term benefit, would irrevocably transform their place from a locale of intimacy and familiarity to something threatening and alien. Therefore, to understand the Corrib gas conflict you have to see the world in a particular way. You have to know the value of place and what that means. You have to know what it is to feel invaded, to be afraid and to have no power to resist. You have to know what it is like to be ignored, to be ridiculed. In north Mayo people fought back and refused to allow their place be taken from them. This therefore is a story of optimism in a world of growing ecological decline and political disengagement. Yet neither the community nor the five men who went to prison were heroes. These were ordinary people caught in an extraordinary situation. They did not seek out this position - these events were thrust upon them. Everything that they did they did because they felt they had no choice. They opposed the Shell project because they believed that they had to do so in order to protect themselves and their families. The five men resisted Shellís efforts to access lands in the village of Rossport because this was the logical consequence of their opposition to the project. They broke an order of the court because that was the logical inevitably of continuing to protect themselves. They accepted imprisonment because they believed that they could not agree to cease their opposition. They remained in prison indefinitely because they could not accept that they must accede to Shellís project. People in their villages brought Shellís work to an end, risking imprisonment themselves, because they could not permit their neighbours to be incarcerated while Shellís project was permitted to proceed. Thus everything was driven by necessity and events. If this was heroism it was heroism of the ordinary kind, heroism that all people are capable of when they feel left without choice. In maintaining their opposition to the project in the face of the possibility that their homes and farms might be seized or that they would be imprisoned indefinitely the men stood by their opposition and were prepared to accept any sanction. This standard of commitment had a galvanising effect on the wider local community and demonstrated that opposition to the Shell project was grounded on conviction and principle. This forced a re-revaluation of the merits of the project on the part of many who previously might have been indifferent. The public ethos of the men, their families and supporters which conveyed integrity and justice drew a compassionate response within the local community and wider afield. The sincerity and patent genuineness of the menís wives (whether one agreed with their position or not) struck a chord. The horrific scenes at the High Court following the menís imprisonment where terrible manifestations of grief and distress were recorded by journalists and photographers produced searing images which created an indelible impression. Bonds of communal solidarity were reinforced in the face of this action by an outside agent. The temptation is to make more of these events than they deserve. But so too is the temptation to make less. The events may have been triggered ostensibly by a single issue but showing through is the enduring quality of the human spirit. We live in a cynical age where motives are constantly questioned and where value is nearly always measured in monetary terms. From the beginning of the Corrib gas conflict, the concerns of locals were dismissed by crude stereotypes. They were accused of seeking greater financial compensation. They were accused of not understanding what Shell was proposing. They were accused of being left-wing ideologues. They were accused of being luddites and anti-progress. The Corrib gas project itself was imbued with some of the most dominant myths of modernity, that industrialisation equals development, that industrial development equals progress, that fossil fuels must always be exploited. In resisting these stereotypes and myths one can discern in this campaign a progression from an initial reaction to the gas proposal towards an affirmation of a particular set of values. It is in this sense that the North Mayo protests were not simply defensive and reactive. They were also assertions of autonomy, participation, and democratic rights. In short, people insisted that they had a legitimate view of their own and a distinct version of what constitutes development and modernisation. I believe that the authentic voice of the Rossport Five heard in this book will stir the conscience of all who read it. Their story is presented so that others may have hope that they too can shape the world in which they live.

|

| BLUE is looking for short fiction, extracts of novels, poetry, lyrics, polemics, opinions, eyewitness accounts, reportage, features, information and arts in any form relating to eco cultural- social- spiritual issues, events and activites (creative and political). Send to Newsdesk. |