|

from 03 february 2002 blue vol II, # 19 edition |

|

|||

A Personal Observation by Robert Allen

I was born in the Belfast Royal Hospital sometime after midnight on October 27, 1956. A wireless somewhere was probably broadcasting Guy Mitchell's 'Singing The Blues' and if I'd known what my parents had done I'd surely have joined in the chorus. In the cold, autumnal air, outside the chlorine-bleached wards, operating theatres and corridors, millions of tiny particles made up a throat-scorching smog which clung to the two-up, two-down terraced houses that characterised the city's place in Britain's industrial empire. Belfast! The capital of the six north eastern counties of Ireland, otherwise known, depending on who you talked to, as 'The Province', 'Ulster, 'Norn Iron', 'the wee six', 'the Six Counties', or 'The Occupied Terrorities'.

Dividing counties Antrim and Down, the Lagan river flows down from the Mourne mountains into Belfast Lough past 180 years of shipyard history. The mouth of the lough, a little way down the hill from the hospital, emanates a smell only a Belfast-born person can know - a sweet, sickly aroma no wind can ever shift. The river at high tide flushes fertiliser and slurry from hillside farms. Waste oils and sewage from hidden outflow pipes colour the river a sickly grey - the colour of the sky on a rainy morning. As the river widens into the lough the grey smear dissipates into the wide expanse of the Irish Sea. At low tide the detrius of this industrial city lies beached on mud flats. On each side of the lough the houses are packed so tightly along rows of identical streets they resemble an impenerable maze.

A few hours later the city springs to life with the clinking of bottles as men in white coats leap sprightly from their electric-powered milk floats. These are the Co-op men. Some milk men urge hugh draft horses along the narrow streets but the horse and cart is the preserve of the tinkers and these won't be about for a while yet. Smoking factories and towering mills and textile workhouses and large department stores and civil service buildings are the landmarks the people know well, for their lives are a cyclical rite of sleep, work, consume.

The encroaching dawn sees them begin another day. The early public houses, bookies, bakeries and grocery stores offer solace, hope and sustenance as the day progresses. Scruffy toddlers and irascible children cover the pavements and roam the narrow streets, curious and trusting, forgetful and forgiving. Mothers scrub and cook and gossip and shop, trailing small, sniffling, protesting children. Corner boys smoke and dream and tease and joke and scowl. The dispossessed, for there are many, carry beaten dockets or hung looks or whiskey breaths and sometimes the world on their shoulders. Trams transverse the city on deeply embedded tracks. Buses trail their long arms from overhead lines along the arteries that divide the city - the Lisburn Road in the south, the Falls and Shankill roads in the west, the Antrim road in the north, the Albertbridge, Newtonards and Woodstock roads in the east. These roads led into Belfast where betrayal and treachery, apathy and selfishness, bigotry and sectarianism, despair and hopelessness seperate the strong from the weak, the survivor from the victim, the optimist from the pessimist and the rich from the poor.

My birth was premature, by two months I'm told, and if I'd known a little about the city I had been born in I would not have been so eager to appear, I might even have changed my mind, if I'd known how.

In the 1880s a 'Royal Commission Survey' on housing stated proudly that Belfast was "one of the best housed cities in the United Kingdom". On the day I was born this notion had become a contentious, politically-explosive, assumption. Modern houses were desperately needed because Belfast was still a young city, less than two hundred years old, and as a thriving industrial magnate for the increasingly disempowered of Ulster's hinterland it was still growing, its continued economic success a blindfold on its Unionist rulers. There was trouble ahead.

Eighteen years later, when I was desperate to leave my birthplace, a survey commissioned by the Housing Executive, showed that 29,750 - a quarter of the city's 123,120 dwellings - were unfit for human habitation. In Ballymacarrett one in two houses were uninhabitable, including the house on Hornby Street my grandparents had lived in since 1911. The Housing Executive had been established to solve the city's "social problem".

The real reason Belfast and its people were in constant conflict had deep, deep roots. Houses were only part of the problem, they were never the cause, anymore than the people who have been blamed. Many, but not all, are symptomatic of the problem. It was and possibily still is their inability to understand they need not repeat the mistakes of their parents, need not agree with their peers, need not adopt negative influences without question from their social environment and need not listen to capricious politicians. Most people hate change but sadly most are like sheep, they are comfortably herded and more easily led, especially if they believe there is something to be gained. That was the way of the first half of the 20th century. Hitler and Stalin, among others, terrorised those with selfish ambition while utilising fear and garnering hope over their respective herds.

In Belfast a man called Ian Paisley realised there was trouble ahead, which he saw as an opportunity for himself. He was among the first Unionist "leaders" of the mid-20th century to build a power base by playing on the fear and prejudices simple-minded working class people feel, like the loss of their job or having nowhere to live. In 1956 in Belfast, if you kicked with the right foot (born into the protestant faith and had good parential credentials), you didn't need to worry about a place to work or somewhere to live. If you kicked with the other foot, the Roman Catholic one, you faced an uncertain future.

I had been born into a society that was very ill and about to become deranged. As I grew up I quickly learned there was a strong blame culture in Belfast, an atavistic guilt, that explained much about human nature and human nuture, for this was a place where both genes and environment describe the man, woman and child. My father, James Allen, had come from County Antrim to find work as a plumber in the city. Like many of his era - born in the bloody aftermath that led to the partition of the country of his birth into six and twenty-six county statelets - he carried his prejudices with him, adding his own narrow-minded attitudes to a melting pot of unimaginable bigotry and rampant sectarianism. I don't know if he was always insular in his actions and thoughts.

His upbringing provides few clues and I don't know if living and working in Belfast influenced his attitudes. I suspect it may have done because Belfast's working class streets were paradigms of fear. He always perceived himself as a strong man in much the same way that my mother, Doris Tweedie, thought herself pitiful and weak.

"Jimmy's bark is worse than his bite," his workmates would tell me when I went to work under him at the age of 16, only I knew differently.

My mother could not control her restless son and I suffered the consequences until I finally left home, embittered but free, at the age of 18. My father's bite was much worse than his bark. He worked hard, as many working class people do, believing the family, rightly so, is sacroscant, bringing in enough money to feed, clothe and house his wife and child. That should have been enough for me, for was I not to follow in his footsteps and become a human cog in the industrial machine once the school system had broken and remoulded me. It never occurred to him that these are basic requirements of life - for everyone. He did not question why he had a job and many, equally competent men, did not. He did not ask why he had a home while other people lived from hand to mouth in filthy hovels. What he did say showed his ignorance.

"There's plenty of work if you get out of bed in the morning, no shortage of houses if you can pay for them."

I knew none of this when I was a child. My ignorance at least was born of innocence. I'm told I was seven pounds something when I appeared, presumptuously, into the world and, when the hospital people decided I was strong enough to leave, my parents took me to the crumbling brown bricked terraced house at 85 Hornby Street, sparking a strong relationship with my grandfather, Thomas Tweedie, a baker by trade, and my grandmother, Rosanne McCoy, mother of seven children. (My father's parents had been dead for a long time.) We lived there for a while, until my parents were awarded a council flat in 'an estate' called Clarawood on the far eastern edge of the city. It wasn't a wood, it was a human jungle. It was a place to get away from because it housed some very bad people.

I didn't realise this until I was three, when I made an instinctual escape. I got on my tricycle, rode over the common ground at the front of our flat to the small farm at the bottom of the hill, beside Beechy River, and followed the bus route the two miles to my grandparents on Hornby Street, somehow knowing that home is where the family resides and family, to a small child, is an instinct that is as old as humanity.

When I was nine weeks short of my fifth birthday my mother dragged me screaming into a state school and two years later into another one because we had moved from Clarawood into a private semi-detached three bedroom house in a place called Orangefield, on the other side of Beechy river. School did not appeal to my sensibilities. It offered cold, authoritarian teachers and irritable, bullying children. I wanted to bury my head somewhere and pretend I did not exist. This life wasn't fun at all.

If you know anything about northern Irish politics you'll realise that a state school is where parents of the various protestant religions - usually methodist and presbyterian - send their children. Parents of children born into the catholic religion could, if they wanted, send their offspring to a state school, but that was a bit like handing a jew over to a bunch of Nazis, so they went to catholic schools instead, which was very like handing a child over to the jesuits. Muslims, and there were a good few of them in Belfast working in the textile industry, had a problem. Their children could never understand why other children kept asking them if they were catholic muslims or protestant muslims, and why it wasn't a joke. The few Asians - mostly Hong Kong Cantonese - in Belfast sent their children to state schools and let them fend for themselves. They did and survived probably because they hadn't a clue what the other lot were about. However if you had got it into your head that religion and schooling were bad things, at least in the hands of Belfast's Unionist, pro-British, rulers, you had a problem, a very big one.

I always loved my mother and it wasn't until many years later I realised how frail she was. She had, for reasons I never discovered, a death wish. I'm told I was a difficult birth, understandably because I came out sooner than expected, and this did her head in. Raising me caused her concern. Children hurt their parents in ways neither understands, except the child doesn't bear grudges or at least not until they are older, but some mothers and some fathers do not appear to possess the necessary parential skills to shake off these flightly emotions, particularly, I would argue, in the protestant industrial world. Children rightly demand love. In Ulster protestant homes they reared them tough. Love was as elusive as the idea of harmony and humility, and as rare of the notion of peace. Sending me off to school freed her to go back to bed and her dreams, whatever they were. Sometimes it seemed to me that as I grew older she was happier when I was out of the house.

It was too late to do anything about it when I realised how wrong I had been. My father was the problem. He didn't understand what was wrong with his wife and he hadn't a clue how he should communicate with his son, except to bark admonishments and criticisms. This was peculiar to Ulster working class protestant homes, a curious christian undertone, a Dutch, rather than an Anglo-Germanic, way of behaving. I sometimes thought I was living in a house of fragile glass. I hardly dared touch anything and everything had to be obsessively clean. Cleanliness and godliness apparently are necessary to get into the place people call 'heaven'. So I was told.

All of us are born without any notion of who we are, what we are, where we come from or why we are here. Simply we are born. We are not born with an assumption or a belief or a history. We continue to evolve, inheriting genes and passing them onto the next generation - if we can. Our parents are a male and female of the species whose biological function is to successfully mate and produce offspring. Their chromosomes and genes mix fifty-fifty. The result is a carbon copy of both of them. It's the sort of thing that goes on all over the planet every second of the day, each and every day, with every species. Reproduction and duplication of the genes.

"Oh he's got his mother's eyes."

"His father's nose."

"His mother's mouth."

"And look he has the same hair as his father."

You might hear: "The little scallywag, he has that same look as his mother when the father's out drinking."

"The father's brains I'd say by the cut of him."

When we are born we do look like our parents but we don't have their experience, their fears and prejudices of life, simply because we haven't lived one yet. Children, we are told, are sponges or magpies and learn so much so quickly. They learn as they experience their environment but they also learn because they have been genetically programmed to react a certain way. Our genes contain a lot of information. Some of it is instinctual. Some of it appears, to the ignorant, as a "gift" from God. "Your child is so blessed." Naturally, however, our creation was more complex and much more interesting than a mere six days on a spiritual computer. If we are musical it is because we have inherited a gene from our parents that gives us perfect hearing. If we are quick-witted it is because we have inherited a gene that gives us swift responses. If we are good with our hands it is because we have a gene that makes sure we stay alive so we can find a mate and reproduce that gene for the survival of the species. In other words we are born to live long enough to reproduce. This makes us selfish, because our instinct is survival. And sometimes it makes us do things, if we ever thought about them as we act, we might never do. Sadly one of those is not choosing when you are born that you don't want to be in this place.

Lucretius was being ironic when he said, "happy the man who knows the cause of things". It can take a lifetime to figure that out. When you are born you strive to stay alive and you do everything you can to do so. When you are a child the world is an big place to experience and enjoy as you grow. Real consciousness begins at seven, and then life becomes interesting.

For me that meant life in an atomised, individualised, insular society where the disadvantaged, disempowered and dispossessed either accepted the misfortunes of birth or decide that someone is to blame for that misfortune. This is not a tangible consciousness in a child. It is something I witnessed and accepted as life, without question. For I knew no different. Is not every child's life the same? Belfast, in the manner of all industrial cities, wrapped itself around me like a warm, protective blanket. Its energy, noise, sights and smell homogenised into a much more tangile entity that existed to accompany me on my daily rites of passage.

During the 1990s Sammy Douglas ran the East Belfast Development Agency in Templemore Avenue. His offices were wisely chosen, located close to the Woodstock, Castlereagh, Beersbridge, Albertbridge and Newtonards roads, five of the six major arteries which socially segregate east Belfast. Reflecting the agency's role as a development agency for all of east Belfast he is minutes away from all of its communities.

A small man in his forties, he had the characteristics of his age - a balding head and protruding paunch - and the enthusiasm of a community worker who didn't let the job turn his head. A soccer fan, he has been a fervent supporter of Linfield, Belfast's senior club with its staunch Loyalist following, since childhood. A father with a teenage family, he showed none of the cynicism and apathy of many of the people he was trying to empower. A native of Sandy Row in south Belfast, he has an astute understanding of the causes of the decline of Ballymacarrett and it is not exclusively a symptom of insular Unionist politics.

"I think many people in protestant areas have undergone an identity crisis. A person's identity is linked to their job and when you take away their jobs you're taking away that sense of identity," he said without any perceived malice towards anyone, until he began to castigate Unionist and Loyalist politicians for being more concerned with the border and the southern Irish Constitution than with unemployment and poverty in their own areas. "I think people realise that they can't depend on the (British) state or the churches or the politicians anymore. There's a growing sense of alienation which is coming from a government that has no interest in us anymore."

Douglas, however, is not alone in east Belfast in his belief that working class protestants have been betrayed by their Unionist masters, that those loyal to the union with Britain simply maintained a protestant ascendancy because they were concerned solely with their own interests, that the Unionists' successful subjugation of the protestant proletariat contributed to the failure of northern Irish socialism. Despite the genuine pragmatism in these thoughts, there is much in the argument that protestants, because they did not get involved in socialist politics, have a lot of catching up to do. This is evident when Sammy talked of his own background. At a meeting of community workers when the subject of the protestant ascendancy came up he responded to what he saw as an attempt to off load some guilt on him.

"Look, I said, I grew up in Sandy Row, which was predominantly a protestant working class area, and we had five in the bedroom of these two-up, two-down houses just like around here (indicating the streets off Templemore Avenue in Ballymacarrett). I was running around to the tick men to borrow a couple of quid a week because my father was unemployed for long periods; he went to Scotland because he couldn't get work in Belfast and I said to these people, 'that's some ascendancy'. The unionist ascendancy didn't benefit the protestant working class communities though, of course, we voted them in. I think many of us were ignorant, we were sold a lie, that we were the people and that catholics were second class citizens. I believed it and so did many but I believe there is a growing realisation in protestant working class communities that we were conned in many ways - there was an ascendancy alright, the aristocracy, the lords and the ladies who had no interest in Northern Ireland, who opposed every political measure that was going to benefit run-down areas. My house in Sandy Row was 150 years old. It was terrible with rats everywhere. Some ascendancy."

The demand for "civil rights", if you listened to Unionists, was not something that concerned 'Loyal' protestants. "We are the people," they told themselves, and it took them a long time before they realised they were socially deprived, especially in Ballymacarrett.

The Housing Executive survey of 1991 revealed that one in ten houses in east Belfast were unfit to live in, with the figure proportionately higher in Ballymacarrett and in estates like Clarawood (where I used to live) and Tullycarnet. Between 1969 and 1973 approximately 60,000 people were forced to leave their Victorian slums. Many of the terraced houses at the Lagan end of the Albertbridge, Newtonards, Woodstock roads were burned out, leaving catholic and protestant families homeless. The years between 1971 and 1973 saw a migration out of east Belfast similar to the one that had brought many of these families into Belfast in the 19th century. There are no accurate figures for the numbers who left because some went west to Galway and Mayo and some went east to settle in the industrial heartlands of England, where everyone from Ireland, north or south, was known as 'Paddy' or 'Mick'. Some protestants renounced their backgrounds and changed their accents, a trick repeated twenty years later by college educated catholics from the south.

The rebuilding programme was slow starting. In its defence the Housing Executive said it built 17,000 new dwellings in the city between nineteen seventy one, including 1572 new homes in Ballymacarrett, and nineteen ninety three. Those figures speak for themselves. This was a political problem. The Housing Executive was in the business of building and renting houses, not solving social problems, even if the first chairman of the Housing Executive was well aware what faced them when he said "the executive must be more aware than an agency for the physical task of building houses. We must build with an awareness of all the problems that go with housing and the social implications of our task". At the beginning the Housing Executive was aware of the limitations of working solely as a housing agency, limitations glaringly obvious in the mid-nineteen nineties. The Housing Executive's Michael Graham was in agreement with observers of community politics in Belfast that "everyone involved in communities now realises that things can't be looked at in isolation, that we've got to look at things from an inter-agency perspective and also from a perspective that involves the community itself."

If communities were taught how to help themselves rather than government agencies sitting back waiting for communities to come forward progressive community initiative would occur more often, he lamented. In protestant east Belfast that was an assumption too far. People with no hope do not come up with community initatives, especially in a climate where co-operation and mutual aid are regarded as "things taigs did".

With a population decline of almost one in five over the ten years of the 1980s, Ballymacarrett was not just an area in decay, but a place where those who hadn't left saw no future for themselves - they were simply waiting to die and if it happened sooner rather than later as the result of a misguided belief in sectarian violence, so what! A place in heaven was always there for the good 'prod'.

Despite the existence of the East Belfast Development Agency, and for over twenty years the presence of the East Belfast Community Centre on the Albertbridge Road, there was an overwhelming distrust and apathy towards community initiatives. That was beginning to change slowly but there was little self-empowerment and any activity was, in the time-honoured fashion of unionism and loyalism, reactive than proactive. Not only is the protestant community in east Belfast atomised by its character, it is also insular in its apathy. The sense of place was being slowly eroded away. In some parts of east Belfast, in the 1990s, there was little community interaction outside of the drinking haunts. Douglas believed the apathy is rooted in the social conditions. "You get to feel the poverty in those houses and it's very hard to mobilise people, to say to them what about trying to do something abut play areas or economic development; at the end of the day some of these people couldn't care about life itself."

When I grew up in east Belfast life was hard for the communities along the Albertbridge and Newtonards Roads, but it was alive. The thriving community-oriented shops that thronged these two arteries, for over one hundred years, are now sepia-blurred memories - victim of urban clearances and a planning policy that has seen multi-purpose shopping malls built in the city centre and in the outlying districts. In Ballymacarrat the shops that remain sell basic foodstuffs and drink. Several small bakers and butchers are still trading but the Albertbridge and Newtonards roads are now lit up with fast food outlets. The commerce that existed in the nineteen sixties has gone. George Mackey, of the Laganside Development Corporation, identified this in 1993. "In some areas, the levels of deprivation are among the highest in the city. Major resources, both public and private, are invested in the area with minimal overall perceptible effect. Local people have an expectation that conditions must be improved and a despair that they will not."

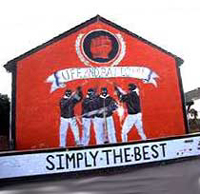

Once an area with a bustling community of public houses, Ballymacarrett now has few pubs to boast about and these, along with the football supporters clubs which sprang up in the 1970s and 1980s are identified closely with the Loyalist movement. Like other areas of Belfast the east has its share of clubs, like the Westbourne Glentoran Supporters Club, the East Belfast Constitutional Club and the Harland and Wolff Welders Club, which, despite their popularity, reflect the past rather than the future.

Observers of community life in east Belfast have noted with irony that if the energy that went into the paramilitaries went instead into community initiatives the place would probably be reborn. Loyalist paramilitarism, if it was about anything other than violence, was about collective action - unlike the protestant religion which is fragmented. Protestantism is about individuality, say social anthropologists who claim to know these things. Protestant/loyalist communities are atomistic, unlike catholic/nationalist communities, which are paradigms of collective action. This is a convenient generalisation but it is true especially in the north east of Ireland. The nationalist communities in the six counties have had to fight back to reclaim their lives and identities. In doing so they have proclaimed to everyone who will listen why a sense of place and belonging is so important.

The 'Loyalist' communities seem unaware that they also need to belong. They don't appear to realise that belonging to a place means participating in community and cherishing the environment. But that's what happens when people are part of an industrial process, are cogs in the wheels of the machine, instead of people who belong to a wider community that involves everyone and everything.

Yet the portents for this duality between the two communities have always been there, that the political and social conditions for disempowerment would eventually manifest themselves in everyday life - in protestant communities. This process was held up because those who wielded influence - Unionist businessmen, Loyalist politicians, Orange Order masters, Masonic leaders, Protestant churchmen - pretended that everything was alright or were unaware of the social changes in their communities. It was as if they were not aware that social decay was inevitable. Were the sociologists of Queens University (of Belfast) not interested in places like Ballymacarrett?

No, they didn't care. The middle classes care little about the workers, and never have done.

If you questioned what was happening, as Ballymacarrett playwright Sam Thompson tried to do with his play 'Over the Bridge', you were marginalised. It was Stewart Parker, another Ballymacarrett playwright, who identified what Sam Thompson was getting at when 'Over the Bridge', despite being rejected by the BBC, was finally performed in 1960.

"We were like members of a lost tribe, thrust before a mirror for the first time, scared and yet delighted by our images, sensing even then that they were much more than a mere reflection. And the mirror was no missionary trinket, but the work of a dues-paying member of the tribe, a man with the plain prod name of Sam Thompson."

Both Thompson and Parker attempted to show the wider world what the communities of east Belfast were really like and to present snapshots of these protestant streets with humility and honesty and humour. Unfortunately the people Thompson and Parker should have been reaching with their work were not in the habit of going to the theatre, in Belfast, Dublin, Edinburgh, London or anywhere else. The social messages Thompson's and Parker's plays contained were lost on their audiences. The Unionist cultural establishment which had been shocked by Thompson's work had nothing to worry about.

And while Parker's early plays were broadcast on BBC Northern Ireland, it was the middle classes who listened in, not the working class protestants of east Belfast. Theatre goers in Belfast were also drawn largely from the educated and propertied classes, so when one woman, with the fruity tones of Belfast's Malone Road, on leaving one of his plays remarked, "that Stewart Parker, he's giving Belfast a bad name" she was showing her ignorance of working class life in the northern Irish city.

Parker, of course, found the comment ironic, if only because it revealed to him that he was following in Thompson's footsteps. "Ballymacarrett was a good environment to come from if you wanted to be a writer," Parker remarked earnestly in 1986, even though east Belfast has produced relatively few creative artists. "You had a struggle with the place because you were told you were British with an allegiance to a monarch, yet there was a feeling that you were Irish. If you managed to get through it, there was a great advantage to draw from such a background and to be able to write British as well as Irish characters. It gave me a wider canvas on which to paint."

What is significant here is that Parker felt the need to leave his homeland. Parker once spoke about his reasons for leaving Belfast. "I think staying or leaving Northern Ireland, in general, is a preoccupation for anyone who comes from there. My first instinct had been to get the hell out, but then the next emotion was that I had to return and come to terms with the place. I had been conducting a private war with it ever since I was born, yet in another way I had a strong atavistic attachment to it that had to be resolved."

Stewart Parker died in 1989 not long after his six part television series Lost Belongings was broadcast. A modern adaptation of the Deirdre of the Sorrows myth from the Ulster Cycle, Lost Belongings is also about a sense of belonging, of identity, of place and essentially of being. This was not just a play about east Belfast. Parker broadened it out to include the wider northern Irish community, placing in perspective the reasons for needing to belong to a place and why identity is so important irrespective of who we are or what our background is. Belonging to a place with the sense of identity that goes with it is a crucial element in Lost Belongings. Early in the first episode, Red Branch, a row develops in the midst of a dozen or so young people while a middle-aged English journalist appears bemused by it all during a party in a Victorian house in east Belfast.

DUBLIN STUDENT: And good luck to him.

GIRL: The usual Provo garbage, the protestant people have as much right to belong here as anybody in the world does, and if they want to stay British, they will, no matter how many murdering bastards try to stop them...

DUBLIN STUDENT: If they're so mad keen on being British, let them go and live in England...

GIRL: If the catholics are such ardent republicans, let them go and live in the south, see how much they like it there...

DUBLIN STUDENT: They'd be a hell of a sight better off than they are in Newry or Strabane...

LIAM: Nobody needs to go anyplace - except for the British Army and their political wing up in Stormont. They're going back where they belong. There's a home here for any protestant that wants to be Irish. But they can't have it both ways, they've a simple choice to make...

GIRL: Aye, get out or get your head blown off...

LIAM: ... they've been led up a historical dead-end for sixty-odd years by a gang of Orange fascists...

GIRL: ...how dare you sit there and patronise a million people, you smug wee shite...

LIAM: ...once their leaders and paymasters have legged it across the water, the ordinary prods will come to their senses quickly enough.

GIRL: My brother was blinded by your Provo cronies, you fenian pig! You think we're going to bow the knee to those animals? Not in a million years, shitface!

LIAM: You can see the problem with asking people their opinions round here.

JOURNALIST: Yes, quite.

LIAM: It doesn't alter the simple truth, though. Which the British media seems to be incapable of recognising.

JOURNALIST: Why do you feel this need to prove that you belong to the place, and that it belongs to you?

DEIRDRE: We have to belong somewhere, don't we? Where else is there?

For those who live in virtual poverty in east Belfast there is nowhere else. Emigration isn't an option.

The protestant working classes of 'Northern Ireland' are in a wilderness - but it is not of their own making. Belfast, along with Glasgow and Liverpool, were the industrial jewels in the glittering crown of the British Empire. In Belfast the protestant workers were the loyal servants of this empire. They serviced Britain's imperial machinery. It was a world they were born to and programmed to believe in. Their loyalty was repaid in the form of jobs. A demographically engineered state was created to protect them and their Unionist masters. A belief system was created to keep them servile and contented. They were told they were the people. They believed they were the people and nothing could touch them. It was a belief they were prepared to die for. Their Ireland was a rich and fertile land. Industrial protestant farmers fed the industrial protestant people. The other Ireland (as they saw it) - of fenians and taigs and priests and IRA men and wanton women - was a backward land of unwashed peasants toiling under grey skies.

The Loyal Lads who epitomise the sectarian violence now associated with Ireland's protestant paramilitary groups are not people who take the time to think about their actions. They are part of a collective which controls their minds, just like the Borg in Star Trek. They have been programmed with a belief system which encourages an insular individual response to anything that conflicts with the mindset of the collective. They have been assimilated into a flawed system. But they do not know it is flawed because they know no better. They are also no different from other industrialised and isolated communities all over the planet. It is easy to apportion blame for their behaviour and even easier to misunderstand it. Fear is a powerful emotion. When it is fuelled by ignorance it becomes deadly.

The protestant working classes took belonging for granted without truely questioning what they actually belonged to. The protestant people of north east Ireland deliberately isolated themselves from the true culture of Ireland, to the extent that many are unaware of the cultural, political and societal forces which are producing a mutation in the rest of Ireland. That imposed insularity has become the death knell of their bigoted and sectarian belief system.

John O'Donohue said: "When we become isolated, we are prone to being damaged; our minds lose their flexibility and natural kindness. We become vulnerable to fear and negativity."

This is what has happened to the protestant working classes. They have lost their sense of belonging. They need to discover a new and deeper belonging - one which will free them from their industrial ties of bondage. A sense of belonging, said O'Donohue, "suggests warmth, understanding and embrace. The ancient and eternal values of human life - truth, unity, goodness, justice, beauty and love - are all statements of true belonging". The need for the protestant working classes of Ireland to belong is now absolute. It is also inevitable.

The longing to belong defines all of us, whether the modern Irish are descended from the Fir Bolg or the Picts, from Normans or Vikings, from Cromwellian soldiers or Scots planters. The need to belong is an essential element of our being. Belonging, however, is not enough without place and identity. The protestant working class are not the only people in Ireland who have lost their identity and their sense of place. Sadly they believe they are the only ones and that is the reason why they cannot heal themselves.

- This is an adaptation from LOST BELONGINGS: A BELFAST LEAVETAKING by Robert Allen

|

||

NOW

NOW

LIAM: ...the simple underlying fact being that the English don't belong here, they never have and they never will, and as long as there's an English soldier left on the soil of this island, there'll be a soldier of the Irish people ready to send him home in a box.

LIAM: ...the simple underlying fact being that the English don't belong here, they never have and they never will, and as long as there's an English soldier left on the soil of this island, there'll be a soldier of the Irish people ready to send him home in a box.