|

from 09 june 2002 blue vol II, #37 |

|

|

by Robert Allen & Anne Ruimy

The morning was sunny, the air clear, the visibility exceptional. The sea was calm and the crossing from Doolin on the Happy Hooker to Inis Oírr uneventful. Approaching the island, still at sea, the reflections of the sunlight became intense, almost blinding, like you'd view a Mediterranean village. The sun's rays were bouncing on the many new houses built in the village above the pier, some painted white, some plastered but not yet painted.

The morning was sunny, the air clear, the visibility exceptional. The sea was calm and the crossing from Doolin on the Happy Hooker to Inis Oírr uneventful. Approaching the island, still at sea, the reflections of the sunlight became intense, almost blinding, like you'd view a Mediterranean village. The sun's rays were bouncing on the many new houses built in the village above the pier, some painted white, some plastered but not yet painted.

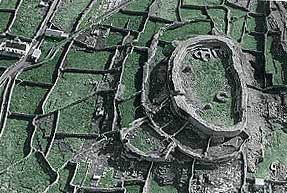

The recent building boom on Inis Oírr is not an indication that the island has been transformed beyond recognition by the 'Celtic Tiger' economy. Protected partly by its isolation from the mainland, partly by the designation of most of the land as a Special Area of Conservation, its picturesque features are mostly intact. Arriving from County Clare the contrast is striking. The village above the pier is a mosaic of houses and little fields bounded by stone walls built from limestone slabs, arranged in diverse structures and combinations, the stones mostly laid vertically and a single stone thick to allow the wind to pass through and to deter animals from attempting to climb over them. These structures are not as fragile as they look, evidenced by the fact that all walls are standing, unlike the crumbling walls of Clare that have to be topped in most places by electric fencing to keep livestock confined. Some of Inis Oírr's fields, their surfaces barely larger than a cottage, support a horse, two cows or four sheep, animals that seem to be always feasting on fresh meadows of thin blades of grass and wildflowers, as if the grass was growing faster than they could graze it. In Clare, the herds of cows grazing larger fields seem to always stay around the spot where they are fed their daily bales of hay or silage; most fields are denuded and show signs of poaching. I like to think that the reason why the Aran islands are still so beautiful has less to do with strict environmental controls than with the fact that insularity breeds love and respect for the land, that should not be abused, artificialised or pushed to its limit. Some of the small fields are sown with potatoes. This early May, the first leaves of the plants are starting to emerge in the meter wide ridges, the lazybeds that unlike their name suggests demand their fair price in sweat, all for two year of cultivation after which they revert to meadowland for a fallow period that can take 15 years. I don't seem to remember that there were so many potato fields the last time I was here five years ago. A healthy sign of Inis Oírr returning to self–sufficiency? From the pier, turning right, passing behind Tig Ned's pub and taking a few turns, we started climbing the deceivingly steep hill on the little road that leads to the cluster of houses of the O'Cualaín family, with our burden of two children and camping equipment. We had come to stay for the week end with our extended family, Roisín and Martín O'Cualaín. Brían, one of their eight children, is married to my husband's sister. Martín didn't hear us approaching. He was bent over, in the fashion of older people who have worked the land all their lives, low on the ground, his torso parallel to the ground. He was digging a square of ground with a shovel, using his knee as leverage, in a corner of the field around the newly built house of his son Ruaíri. I thought he was digging a garden patch. He explained that he was digging a hole for a septic tank. A hole for a septic tank, through the limestone pavement, with a shovel, I asked in amazement? "I've a pick," he paused. "I left it abroad, in another house." The work is eased by the fact that he had already reclaimed the ground from bare rock, years ago. To make the field from the mostly bare limestone pavement still visible in some fields around the village, but now mostly relegated to the back of the island, he first had to break the surface of the stone, then bring in sand, then seaweed. Nature did the rest and seeded the sand and seaweed mixture that was able to cling on to the broken stone, turning it over the years into a thin layer of sandy soil. Roisín invited the children to her house for a glass of milk. "Do they like milk from the cows?" she enquired, because some of her grandchildren only drink milk if it comes out of a bottle. Their house was built by Martín's father. "One of the first houses that was built," he tells proudly, as if the cottages built earlier didn't really count as houses. Indeed it is an early example of a bungalow, albeit surrounded by bucolic scenes including an upturned curragh in apparently working condition, a donkey cart starting to rot away, hens of all colours and sizes, well fed cats, and a myriad of narrow flower beds around the house, stone sheds and garden walls. And in a field, looking over a wall at the house and visitors, a cow and calf oddly sporting the twin yellow plastic ear tags now made compulsory by agricultural regulations, whether one is farming the fat land of the Golden Vale in central Ireland or the barely covered rock of a tiny island in the Atlantic ocean. "We have one cow milking," Roisín explained. "The calf isn't able to take it all yet. The hens have been getting some of the milk." Along with the flowerbeds, keeping the hens is Roisín's job. "You've to watch the hens, they lay outside, under bushes. One time twelve chicks were born, they all survived. Most of them were cocks. We kill them, there's not much meat on them but they make nice soup. One time, several years ago, we decided to get rid of the hens. They don't pay. You've to feed them, crushed oats and layers' pellets. But it was too lonely without them, we got them back." They also have a goat roaming somewhere on the island. "We don't know where she is, Martín doesn't want her to have kids. She used to have a fair amount of milk. Martín doesn't like killing them but the meat is delicious, did you ever taste it." No, I laughed. Farming is what the inhabitants of Inis Oírr have always done, and fishing. Since the start, and despite the difficulties, farming and fishing have been turned towards the outside, the mainland. When Roisín and Martín were young, self–sufficiency – keeping one cow and a calf, a few goats, hens, growing potatoes and a few vegetables – was not an aim but a necessity. The two small shops were barely stocked with tea, sugar, butter and tobacco, and money was scarce. It had always been necessary to produce cash crops – potatoes, seaweed for iodine production, fish and shellfish in the old days – because fuel could never be found on the island, no matter how hard the fishermen and subsistence farmers worked. Fuel, usually turf, had to be traded with the outside world. If the Aran islanders have always looked across the sea, towards Connemara and Clare, it is because they needed the turf to keep fires burning in the kitchens. Such habits are not easily broken. What has started as a necessity has gradually become something of an absurdity. Most people kept cows and a few calves in the 1960s. If the "cattle jobber" didn't come in the summer, the men had to take the calves to the mart in Galway. By the time they had paid for the fare and one night stay in Galway, it was barely profitable. Now membership of the EU has reduced price fluctuations, and thanks to subsidies subsistence farming has all but disappeared. As for the fish, ah, it was getting scarce anyway. But the sweat of generations of hard working men like Martín and his ancestors who turned the limestone rock into wildflower meadows is now exported as far as the Middle East and the Persian lands in the form of beef cattle. In the 1960s, Martín was able to grow a surplus of two tons of potatoes per year to sell to Clare. As he didn't have enough sacks, he had to buy them from Clare – and pay for freight. Then he'd have to pay again to send away the sacks full of potatoes. At that time, imported potatoes from Cyprus started to be found in the island's shops. Twenty–five years ago, Ruairi O'Conghaile took over the shop from his father Sean who was "a great businessman, but he didn't move with his time," as Roisín put it. "Now it is like a supermarket," she says cheerfully. It is not as if Martín and Roisín are unaware of the element of unsustainability of their farming life. Along with a few neighbours, they tried once to farm organically. "We're in REPS, we have 26 acres," Roisín explained. "It keeps the cows going, as long as Martín sells the calves. At the moment we have three cows, two calves, and three yearlings. The yearlings will be sold later in the year. We had a bit of worry, we tried to go organic for a while. A man from Tipperary came, took a calf, said he'd come later on to take the other ones. He never came back. Martín worries a lot. I was saying 'can't you buy in stuff' but he doesn't like that. We got in special food, crushed oats for the fowl, barley for the cattle. We wouldn't even sell the eggs, there was not enough. We did it for three years, you have to pay so much each year for the feed, the freight, the price goes up all the time. Growing the feed ourselves? Martín was getting on his 70s, Ruaíri was building his house. And there were so many blasted forms coming in! A girl would come in every year, walk the ground. We said we'd grow more soft fruit, but Martín isn't interested in that sort of stuff. Now we've left organics, it's too h ard to go organic. Two of our neighbours went organic, they gave up. It would have paid if we got the animals to the mart. It's alright for people on the mainland, it's a very good idea, you need to be near the market." It's coming up to election time. But the cortege of politicians and their supporters who come to Inis Oírr for a day trip of canvassing are not taken seriously, they are the subject of kitchen table jokes. The really powerful men, the ones for which a mixture of loathing and respect is reserved, are the local businessmen who control the infrastructure. The operators of Doolin Ferries, who can put up the price of freight at will, so that it costs EUR30 now to bring a cow, a yearling or even a calf to the mainland. The men in charge of road works, distribution of gas cylinders, those who have the power to bring in a secondary school on the island or can afford to invest in wind–farms. Roisín was sent to Inis Oírr to serve as the island's nurse and mid–wife. "October 1961 I came here, that's 41 years now. I met Martín a few months later. His parents were old." Roisín didn't elaborate on their encounter, what brought them together. Her sentence ended with an unformulated "and that was that". Later she explained why the Aran islands are populated mostly by men, bachelors, and why the women that come from Clare, Galway, Donegal, Dublin, America, even Guatemala and end up "marrying on the island" are a godsend. "The women left, for America and other places. Some wouldn't be attractive or would be too fond of the drink. Three men were needed for a boat, in the old days when they went out fishing. It wouldn't be easy for a man to bring a woman when there was three men at home. They were all bachelors, all virgins too. There wasn't much talk about sex, there was hard work to do on the farm and no tractor. They just forgot about it. They had pints of Guinness, went to races, played cards. The religion kept people on the straight and narrow." Roisín then talks about her childhood, her brothers and sisters, her travels. She talks a lot about County Meath, where she comes from. I have a feeling that she still belongs there. "At home in Meath we grew peas, beans. We tried peas here one year, it was hard work, they need good soil. They grew well. Now we only have the usual, spuds, onions, carrots, and cabbage around the house. Since after WWII there has been a lot of changes in Ireland. It used to be mixed farming. Now it's all cows, or all tillage." By that time Martín was long gone out of the sitting room. He probably avoids staying around when two women talk. Over the course of the weekend the only time I could hear him telling stories was when he talked to my husband and Ruaíri in the kitchen. I would sit in an armchair taking notes, sometimes asking a question but not entering the conversation, afraid he would leave. On Sunday morning he was talking about potatoes, the new varieties he tried. "Kerr Pinks I tried, in a new garden. They need heavier clay. I've tried several kinds, I'm back to the same. The 'dates' Up–To–Dates from Donegal. There's a saying: 'put them down early you'll get them no matter what'. But they don't last out. They do be hard, they're not very good for the latter end of the year." My husband asks about rye, is it true they used to grow rye after potatoes? "At that time there was no manure, it was all seaweed. There was a lot of earth after potatoes, the ground was broken up. We grew our own, most people grew rye for thatching. That was before there was any tourists. It was harvested in summer, we pulled it up with the roots. We made a small bundle, hit it on a stone to take the seed out." Martín describes the different techniques in gestures as well as words. "There was a lot of work attached to it. I used to be thatching a lot of houses. There is a picture in Ned's of a house I used to be thatching, near the shop, that's the house where I was born. I was too busy to keep two houses going. I'm sorry I let it go. The co–ops are growing a bit of rye, there is some small grant to keep it going. There is a house near the beach, the father gave it to his son. I thatched it before. Now some lads from the mainland took the thatch down. They thatched it with rushes. After a couple of years it turns black. It's not as nice."

Arriving at Kilronan Pier through a thick mist on the Aran Flyer from Ros an Mhíl in Connemara, Árainn was like nothing I had been prepared for. The island of my imagination clashed with the island of my reality. As it was October the tourists had gone, leaving behind a community about to settle down for winter. I accepted a seat in one of the small buses that ferry tourists to their destinations in the hotels, hostels and bed and breakfasts that characterise Kilronan and its hinterland. The bus driver wasted no time speeding around the horseshoe–shaped pier, turning up past the American Bar and out of the village. I had little time to take in the surroundings, the drystone walls and the crumbling 19th century houses, when the driver announced my stop, telling me to take the sloping road that forked away from the main road. "That's Mainistir," he said. I had been invited to Árainn by Dara Molloy, a former priest living with his partner Tess Harper a lifestyle others would find idealistic. Dara had given me directions to their home – a few miles from the village on the rise towards Kilmurvy. He told me it was thatched so I knew it would stand out. The islanders of Árainn share their Connemara neighbours' love of the modern bungalow. As I walked down the road I passed several bungalows. The road turned sharply and I passed more bungalows and then a row of old empty houses. None were thatched. Then I saw it, dirt gold streaming over a large two–storeyed square house. Dara's dwelling couldn't be different. Sitting on the hill sloping towards the mainland, the house, polytunnel, sheds and gardens epitomise the low impact, self–sustainable environment they sought when they built the house meitheal–style a few years before. Ducks and geese run around the place. Seaweed decomposes in the sandy soil. An old working tractor sits at the gate. I settled in easily. I took to the kitchen which dominated the two storey house, cooking whatever food there was to be found. This was a mix of bulk food (flour, muesli, grains plus jars and tins of various foodstuffs from peanut butter to molasses) and organic food (stored potatoes, onions and whatever was still growing in the gardens). There's something very gratifying about cooking and eating food you've picked out of the garden moments before, especially salads, leaves and roots. Most nights before dusk I went collecting herbs to make tisanes. Dara and Tess have a prayer hut at the bottom of the garden overlooking the mainland. I used it to meditate and chill out. Sometimes when I was in the garden I used it to escape from the sudden showers that occasionally lash the island. On most days you can see the shape of the Connemara mountains and the outlines of the bleak landscape and the growing Galway conurbation. Other days the mainland is shrouded with low–lying clouds and a drizzle that drifts relentlessly across the land. When the rain clears, the clouds part, revealing a patchwork of blues. The primitive in me likes the weather when it is like this. Stormy but clear, no rain. There's more energy about. The rain dissipates the energy of the storm and then the cycle begins again. On a clear day you can see the Mayo, Galway and Clare coastlines, Achill island to the north, Connemara's Twelve Bens mountain range to the east and the cliffs of Moher and the Burren in Clare to the south. This gives the impression that the islands are closer to the mainland than people imagine. Islands always seem closer than they appear and it is only when you've rowed over to them or even travelled in a powerful boat that you realise they are much further away, over turbulent seas. The 40 minutes on the Aran Flyer boat can be a bumpy ride even on a calm day. It's coming up to Samhain, the celtic harvest festival, a time when the earth has given up her fruits, the turning of the season, the seasonal journey from light to dark – a time to celebrate. On the mainland this celtic festival is celebrated by the few who know why, on the Arans it is celebrated by everyone in some form or other. To celebrate people dress up in clothes they hope no one will recognise them in. The tradition says that those who dress up are not allowed to talk. People are also allowed to go into each other's houses and make themselves at home. Usually the adults go to the pubs while the younger children go to the houses and the older children hang out. The idea is that there are two worlds, the outer world and the inner world. If you dress up you become part of the outer world and escape the other world. This is the kind of lived spirituality that attracts people to celtic ways. It also invigorates those with celtic sensibilities – like Tess Harper. When she set out on the spiritual journey that would bring her closer to the natural world it brought her in contact with her anam cara, her soul friend, her kindred. When she left Maynooth college where she had successfully completed a degree in Theology, English and Philosophy she headed for Árainn, knowing only that her instincts were taking her there. "My aims, as I look back on it, were threefold: to be as independent (of systems as I see it now) as I possibly could. To live close to the land and in the heart of nature. To live a spiritually based life," she said, remembering her teenage longing to belong to a world that celebrated nature. The moment she knew she belonged to this natural world has remained with her. "I'm sitting at the back of the classroom in the Holy Faith Convent School, Glasnevin, Dublin. There are twenty–eight students in three rows. I look out of the window to where I can see the tops of the old trees. I long to be outside. What is going on in the class does not interest me in the least. It has been five years of this, a survival course, an endurance test – to say nothing of primary school. I am sixteen years of age. Thankfully, a teacher of another class has intellectually adopted me. I find my soul finally nourished by Camus, Sartre and Dostoevsky. These books I read under the desk while the class goes on. This does nothing for my french, maths and latin, but they were sorry causes anyway." In five years of secondary school education Tess went through the motions, valuing only poetry, prose and drama. The rest meant nothing to her. She when completed her exams, cramming to pass them, she realised she had learned nothing at all. "Later, at least, in Maynooth College, I felt I was directing my own course," she said. "I simply missed lectures that did not stimulate me and devoured the rest. My time was my own to do what engaged me." "Yet as I had once looked longingly at the tops of the trees from the schoolroom window, by third year in college I would be gazing longingly at the road west – to Galway, and more specifically, to Aran. For that was where I was headed. With an instinctive certainty at the age of 19 that baffled simply everyone, I packed up as soon as I had an honours degree and went to metamorphose my head full of ideas into earthen compost from which something could grow." Her path had been mapped out by others. She would become a teacher. She had different ideas. On Árainn she got to express her creativity, doing a variety of jobs – retreat work, workshops, lectures, knitting coloured jumpers, designing greeting cards, editing and layout computer work, writing, – whatever she could put her hand to. When she arrived on Árainn in 1985 the real learning began. She learned organic gardening. On the Aran Islands that means collecting seaweed to manure the shallow soil. It means companion planting and rotation. She learned animal husbandry – how to keep ducks, chickens, goats, geese and sheep. She co–founded The Aisling Magazine which she co–edits with Dara Molloy. She learned to build a stone house. She learned carpentry. For Tess these were the real learning years – "of hands–on living, of learning many skills and experiencing the intricate inter–relationships between many many things". Her celtic soul was honed in the furnace of life. This was the lived spirituality. "The theology I studied in Maynooth has long since gone into a compost bin and the soil that has replaced it is refreshing and fecund. There is an inherent spirituality in all I've done on Aran, in all the tilling, sowing, reaping, the chasing of sheep, the loving of goats, the building. It is a spirituality that makes a nonsense of all the dogma and doctrines I had learned. It makes a nonsense of religion." She didn't know when she left Maynooth what she was letting herself in for. This was no hippy dream. There was, she said, "no set course, no pre–written map, no 'Guide to Wholesome Living'. It is there for the creating and it is far from simple". In 14 years on Árainn she constantly challenged herself, asking questions, demanding answers mostly of herself. She consigned the concepts and practices of "development" and "progress" to the "intellectual compost heap". She wondered how to get the balance right "when so much in our western society is chronically out of balance". She questioned the role of technology in the natural world. She juxtaposed the conflicting ideas of sustainability and economics. The answer, she realised, was always the same – every decision we make has to be a personal one.

"What nappies to put on the baby? What mode of transport to use? What meat to eat or not eat? What fuel to use? The list goes on and on. Each choice requires a thought–out decision. At this point in my life I do not believe in a definitive right and wrong answer to these choices. The situation, environmentally, socially, economically, is far too extreme for simplistic black and white solutions, yet I do feel the integrity of the choices we make, the quality of the thought we put in and the harmonising of our choices with our inner self – these are the things that can count and that may make a difference in the world.

"I have made my home in Aran. When I first decided to come here, a college lecturer predicted that I would not last the first winter. Yet Aran is home for me in ways that Dublin never was. Much as I love Dublin, especially its people and their wit, Aran provides a landscape that knows my name, that eases my spirit and captures my soul. I belong here – not necessarily to the people, for blood does run thicker than water and I'll always be a Dub and a "blow in", but I belong to this place, these fields whisper to me and their song makes me smile." Unlike the seafarers who stumbled upon the Arans or the celtic priests who were called there by their deity or the writers who searched for the primitive or the academics who sought an inner truth, Tess Harper made a conscious decision to create a life for herself on Árainn. She came to stay. Tess survived the first winter because she found other kindreds who had been drawn there for similar reasons. One such kindred was Dara Molloy, a priest from Dublin who had begun to question the role of modern religion in Irish life. He arrived on Árainn in January 1985 with no particular plan: "I wanted space to allow my life to evolve without being manipulated by various institutions and needs defined by other people." He brought with him some spare clothes, books, a typewriter and a stencilling machine hoping that he could do some writing and some publishing, and keep in touch with people. He rented a house for £15 a week, and for the next ten years this was his home. He had been inspired by the celtic monks, like Colmcille and Enda (or Eanna), who had come to the Arans millennia before. "I wanted to live in that tradition and for me that meant living in close relationship with the earth and being aware of the relationship in general with everybody and every thing and to work at that relationship so that it was right and wasn't abusive or disrespectful and so that I found my right place – like when you floated me where did I float rather than tying me down and trying to regulate me and control me – trying to find my own place in the world. Part of my way of life was to offer hospitality to other people who were searching and wanted to become free. I was only in the house for two months on my own. After that I always had people living with me. Over the years there have been thousands living with me I'd say. I never count them but all the time there are people coming." Gradually Dara and Tess began to build a life "outside of the social structures that keep people in their place". This included being able to grow their own food and domesticate their own animals. Not long after they had settled, they had a system in place which was beginning to fulfil their needs. After five years they were becoming self–sufficient. "Our emphasis has gone into providing food for ourselves so that we don't have to go to the shop and we've really worked hard on that. We grow anything that will grow – we have potatoes and vegetables all the year round. We have our own honey, our own milk, our own eggs and our own meat as well – sheep and goats which we kill but we don't breed them to kill them. We don't eat meat every day or anything like it – possibly once a week," said Dara. The animals play an important role in their system. As well as providing animal manure for the compost used on the land they become an integral part of what is a functioning ecosystem, particularly the food chain. For example, the ducks eat the slugs which feed on the vegetables. And the humans, being at the top of the food chain, eat the animals but as Dara stressed they do not breed the animals for slaughter, for meat. "If you have animals they breed and you can't feed them all, so you have to kill some or give them away. It's on that principle that we kill them. It's not for producing our food specifically. We only kill what we can't keep and we only eat what we kill so if we don't kill it we don't eat it. We don't have animals for our food. We don't have them for meat. We have them for eggs and milk and for wool." When they built their own house on some land on the eastern slopes of the island, a few miles from Kilronan, in Mainistir they transferred the system. "We have very small pieces of land," said Tess. "In one garden we use a crop rotation method, brassicas, root crop, and others including lettuces, beans, aubergines etc. We sow a small field of potatoes every year and our polytunnel keeps us in tomatoes all summer." Their garden now provides cabbages, kale, onions, carrots, leeks, beans, peas, potatoes, cauliflower, broccoli, spinach among others and sage, fennell, mint and lemon balm for herbs. The polytunnel allows them to bring on seeds in trays and to have winter greens and tomatoes in summer. Ducks, chickens and goats, geese, dogs and a cat wander around the place. "We grow enough vegetables to keep us going all year round," she said. The Aran Islands are not easily defined despite the efforts of many gifted writers. The atavism that drew Synge to the Arans a century ago in search of the primitive might have been selfish but it was no greater than the impulse that attracted Colmcille and Enda and no lesser than the lure that brought the many academics like Tim Robinson who have studied the islands and its people. Aran has featured in the myths of our imaginations for millennia, and even today people still talk of another Aran, an island in the mist, an island few have seen – the mythical island of Hy Brasil. Early maps placed it out in the Atlantic, later maps south of the Arans off the coast of Clare. Known in Irish as Árainn Bheag or Little Aran and in English as O'Brasil from its Norse and Irish roots, hy the Norse name for island, breasail (or Brazil) the Irish name for reddish substances, this island features strongly in Irish folklore. Roderic O'Flaherty wrote about it in his 1684 book A Chorographical Description of West or H–lar Connaught: "Whether it be reall and firm land, kept hidden by special ordinance of God, as the terrestiall paradise, or else some illusion of airy clouds appearing on the surface of the sea, or the craft of evill spirits, is more than our judgements can sound out." It's likely that those who heard about and sought Hy Brasil were looking for the Aran islands. You can imagine what these islands must have looked like hundreds if not thousands of years ago. So near yet so far. Sea travellers from the Iberian peninsula and from the Mediterranean countries frequently travelled to Ireland's western shores. If you look at a globe of the Earth you can see how they would have ended up on the Arans first or even passed these islands in a storm. What you cannot see from a map are the reasons why these islands, particular the largest island Inis Mór or Árainn attracted druids, hermits, monks, priests, poets, writers, dreamers and utopians. To see that you must go there. The Aran Islands have a magical quality about them. Everyone who has been there has a story and for most that story is fantastical because people see in the Aran islands what they want to see. Tim Robinson was so moved by Árainn that he wrote its history, concluding with an apology. "Whether it be the terrestial paradise, an airy illusion of clouds on the sea, or the work of delusive spirits, I have brought back a book as proof that I was there." Aran attracts romantics, dreamers, artists and writers because it is a place of the imagination, just as Hy Brasil was. You see what you want to see when you travel to these islands and sometimes you see a little more if, like Dara Molloy and Tess Harper, you decide to make your utopian visions come true. They have done this by marrying their romantic idealism to the pragmatic realism of the natives, utilising the living memory of the islanders, their knowledge of the land, the ancient skills, traditions and stories, without which no–one could survive on Aran as Synge so tragically observed one hundred years ago.

|

|||