|

from Fall 2001 blue vol II, various editions |

|

|||

|

Pieces on the growing crisis by Robert Waldrop, Christina Lamb, and Robert Allen

The starvation begins in Afghanistan.

Again I must ask the question: Will we feel better in the spring when

millions of Afghans have died of starvation and exposure? Elsewhere I

have asked this question, and it has been ridiculed. "Why, America

would never allow something like that to happen." Well, as a matter

of fact, that is exactly what we are allowing to happen.

Here's a story from one of Afghanistan's forgotton places, where 40

people die every night, a toll sure to increase as America goes back

to sleep, once again turning our backs on the consequences of our

national actions.

top

They call this 'the slaughterhouse'

A DIRTY grey blanket on the hard desert ground is all that is home for

Bibi Gul and her family in the new Afghanistan.

"The sky is my roof and the earth is my floor," she said, gesturing

across the dust-swept plains toward the minarets of the ancient city of

Herat. But the words from her chapped swollen lips are of bitterness rather than

romance.

It is more than a week since she and her five children had their last

meal - a begged bowl of rice - and on Friday she woke to find her

two-year-old son Tahir stiff and cold, frozen to death in the rain.

While the West celebrates the surrender of Kandahar and the collapse

of the Taliban, here in Maslakh camp in western Afghanistan there is

no celebratory slaughtering of goats or distribution of sweets, but

only weeping and funerals.

It is a place that has been largely ignored by Western governments and

aid agencies; harrowing images of the starving and dying have not been

seen in the world's newspapers or on television because journalists

and camera crews have been elsewhere in Afghanistan, concentrating on

the war. But because it hasn't been seen in its vivid awfulness

doesn't lessen the terrible suffering that goes on here.

Every night as the temperature dips well below zero, as many as 40

people die from cold and starvation. In the six cemeteries scattered

through the camp, many of the piles of stones marking graves are so

tiny that it is clear most victims are children and babies.

Bibi Gul and the other tent-less people of Herat are the refugee

crisis that the aid agencies were all predicting two months ago, but

inside rather than outside Afghanistan.

Hundreds of thousands of people are sleeping in the open, having fled

drought and famine in the north and central parts of the country that

before the war were completely reliant on foreign aid but are now cut

off by the winter.

At first sight Maslakh looks like any of the other vast Afghan refugee

camps scattered around Pakistan and Iran, though it is chilling to

discover that its name means slaughterhouse, after the abattoir that

was here in the days when there were cattle to slaughter.

Set up four years ago for those escaping both drought and fighting in

the north of the country, the camp's early inhabitants have built

mud-brick houses. Further on there are row upon row of tents, and occasional

feeding stations at which boys queue on one side and women on the

other, waiting for hours for a bowl of unappetising grey gruel made of

sugar oil and flour which is the daily ration per family.

Along the road towards Iran that passes through Maslakh, it takes

almost 20 minutes by car to reach the end of the camp which, according

to Faghir Ullah, the camp administrator, now houses 800,000 people,

though a survey by the French agency Medecins sans Frontieres, which

has a clinic in the camp, put the number at 300,000.

The true figure probably lies somewhere in between, but it stretches

for miles in ever-descending human misery as tents turn to plastic sheets

pinned to the ground, and then to no shelter at all.

These latest arrivals, people who have come since the Taliban started

to collapse a month ago, are mainly Hazaras, Uzbeks and Tajiks. Sitting

on blankets on the ground in their colourful garb of purples, turquoises

and pinks, with round-cheeked faces, at first they looked like market

traders.

But as I got out of the car, the first journalist to visit the camp,

it quickly became clear that something was wrong. Many of the people were

not moving.

The children were not playing, not even crying, and many were too weak

to walk. Some sucked at their clothes and hair, seeking nutrition

anywhere. Others lay in bundles on the ground. Old women stretched out

hands, fingers blackened and eaten away by frostbite.

Walking through, hands grabbed at me.

"A tent", "a sheet of plastic", "a piece of bread", came the pleas,

voiced through parched lips while

women thrust small babies at me, sobbing. Not one had any food; all

claimed not to have eaten for more than a week.

I have been to most of the big Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan as

well as many refugee camps in Africa but I have never seen people in

such harrowing conditions. One man, Lal Mohammed, led me to his dying

wife, shivering under a blanket and moaning occasionally. Their

12-year-old daughter Mariam died on Thursday.

"Imagine not being able

to feed your children or to keep them warm, to wake up and find them

dead," he said,

"please help us, we have lost everything, even our dignity."

Most come from the northern provinces of Faryab, Ghor and Sar-e-Pul as

well as Ghazni in central Afghanistan, mountainous places to which the

World Food Programme was giving food aid but stopped because of the

bombing. Now their villages cannot be reached because the passes are

cut off.

All told the same story.

"We had a good life," said Lal Mohammed,

"but

then four years ago the rains stopped and our crops could not grow. We

had no food so the cows and goats died and we ate them but they were

nothing but skin and bones. Then there was nothing to eat but grass

and even that died." Zarha Hussaini, a single mother of five, whose

husband died of tuberculosis six months ago having twice been

imprisoned by the Taliban, handed me her nine-month baby who weighed

so little - less than my notebook - that I almost dropped her.

"We

sold everything to come here as there was nothing left but sky and

earth," she said. During the 25-day trip by foot over the passes, then

by truck, they lived off grass and sucked water from fungus scraped

off rocks.

One can only wonder at conditions that would persuade people to give

up all and walk for as long as a month. But Zarha, like many of the

others, was told by the lorry drivers that they would have free food

and housing in Herat. Instead they arrived to find nothing. The overwhelmed camp

authorities have refused to register them which means they have no

right to the tents and gruel.

"They just tell us to get out and beat

us and even the children if we do not move from the registration

office," said Bibi Gul, who came 10 days ago with her four children,

her blind husband and a group of five families from Ghazni.

Already three children of their party have died.

"When we woke they

were all wrapped around each other," she said.

One difficulty is that the new administration of Ismael Khan, the

Mujahideen commander who took over as Governor, does not yet have the

officials in place. Also there is so much poverty in Herat that even

non-refugees are registering. But there is another problem too. One of

the three funerals that took place in the morning of my visit was for

Neclayu, a 35-year-old Pathan mother of three who had died of cold in

the night.

My guard spat on the ground and pulled a black turban off one of the

mourners. "Taliban," he said.

Many of the tent-less people are Pathans who fled when Herat fell two

weeks ago and are regarded with suspicion by the local majority Sunni

and Shia population who fear that once the Americans leave Afghanistan

they will try to recapture the city. Some of them are armed - we

watched one group trying to shoot birds with Kalashnikovs.

There is also an absolute lack of resources.

"We don't have enough

food for the old population, let alone the newcomers," said Faghir

Ullah, the camp administrator.

"We know people are dying but we have nothing to give them."

"The world made us lots of promises,"

Afghans are used to surviving on little. After 23 years of war and

four of drought, a daily meal is an unthinkable luxury and most villagers say

they can survive on a piece of bread a week. Anyone else would have died

already.

There is anger that the outside world keeps talking about Afghanistan

yet seems to them to be focusing only on ousting the Taliban and Osama bin

Laden rather than tackling the conditions which led to them taking

over the country.

"When the Taliban fell we thought

the international community would help us," complained Zarha.

"I'm so angry and depressed I even dream of

leaving my children here and walking away. If you are a mother can you

imagine ever saying that?" Pushing her veil off her hair, Bibi Gul

said: "Now I can show my face whereas

under the Taliban I wouldn't dare walk around like this or I would be beaten.

But what is the use of that if every night you go to bed with empty stomachs?

"We thought after the Taliban that life would be better, but now I

don't even know if we'll survive."

top

How To Help in the Land of the Free

This is the reply I got from the White House when I

emailed them about Afghanistan:

From: Autoresponder@WhiteHouse.GOV

Thank you for emailing President Bush. Your ideas and comments are very important to him.

If your message is about the September 11 terrorist attack on the United States, please click go

to www.whitehouse.gov to learn more about the American response and to receive or provide help in the recovery efforts.

As the President said recently, one in three Afghan children is an orphan and almost half suffer

chronic malnutrition. He has asked American children to help Afghan children by making contributions of one dollar individually or collectively to:

America's Fund for Afghan Children

For more information, go to www.whitehouse.gov/afac/

Unfortunately, because of the large volume of email received, the President cannot personally

respond to each message. However, the White House staff considers and reports citizen ideas and concerns.

Again, thank you for your email. Your interest in the work of President Bush and his

administration is appreciated.

Sincerely,

However, this is the reality:

When I saw the dead and

dying Afghani children on TV, I felt a newly recovered

sense of national security. God Bless America.

The school claimed Katie's actions disrupted student

learning and a Kanawha County Circuit judge upheld the

suspension. The West Virginia Supreme Court on

November 27 voted 3-2 not to consider Katie Sierra's

petition to prevent the lower court from

"continuing

to deny her freedom of speech". Her attorney says

federal court and other legal options are being

considered. Media reports of threats Katie's received

are true. She's being educated at home (in a program

paid for by the school) because of those threats (due

to her parents' concerns, and the fact the school

can't guarantee her safety). She says she'd prefer to

be in school.

INFOSHOP.ORG:

Can you tell us a little bit about

yourself?

KATIE SIERRA:

Let's see. My name is Katie. I am a

former student from Sissonville High School. I'm a

15-year-old 10th grader. In my spare time I go to

shows, read, and write poetry.

I:

Why did you get suspended from your high school?

KS:

I was suspended for wearing a t-shirt that spoke

of political views. Also, for having possession of the

flyers in my purse.

I:

What did your T-shirt say?

KS:

Well, there's more than one. The one I got

suspended for said: Racism, Sexism, Homophobia ... I'm

so proud of the people in the land of the so called

"Free". Then the next week after my principal allowed

me to wear them again, and then made me take it off

again said: When I saw the dead and dying Afghani

children on TV, I felt a newly recovered sense of

national security. God Bless America.

I:

What happened in court?

KS:

Besides staring at Mr. Mann's (school Principal)

strange comb-over I didn't win. I don't really know

why. At least everything I said was factual, but

everything Mann said was opinion or hearsay.

I:

Are you appealing the judge's decision?

KS:

Yes, we'll be going to court January 25. State

Supreme turned it down ...but I'm not giving up!

I:

How do you feel about the authorities telling you

that you have no rights?

KS:

It makes me feel like total crap. I mean I think

it's crazy. Everyone else in that school can say how

they feel towards certain things, unless you have

something no one agrees with. I just don't think that

is fair. If I could go back to school for a day. I

think I'd probably wear duck tape over my mouth with

"I have no rights"

printed on the front. I think that

might be quite humorous.

I:

Why did you decide to start an anarchy club? Are

other students interested in joining it?

KS:

I think we were pretty much a group already. I

mean I know we were a group. At the time we didn't

have a name. And there isn't anything for us to join

at SHS. So I was thinking since we are all interesting

in Anarchy and whatnot things it would be a good idea.

I read about it on Infoshop ... that's how the idea

popped into my head. Yeah, there was about 15-20

people who wanted to join.

I:

If your club existed, what kind of projects would

the club be working on?

KS:

It was mostly for us to learn and discuss things.

We had somewhat started a zine – it isn't really

finished. We were going to work in some soup kitchens

on the weekend. Just a lot of different things. Have

people come speak. Possibly a Food not Bombs group.

I:

Tell us about the zine you were working on?

KS:

It was going to be called the Anny. There was four

of us working on it. We were only going to print no

more than 30 copies of it. Honestly, we didn't want

anyone besides people in our uhh "freak/punk" to know

about it. It was going to be about things that happen

in our school, city, state, country, world...blah blah

blah and how we felt. The first copy was never

finished so I'm sure there would have been more.

I:

When and how did you first become interested in

radical politics?

KS:

I don't really know. I mean I think I've always

been pretty interested. It might have been my friends.

Most of them are older than me and I guess I just

learned a lot from them.

I:

What's your opinion on the current war?

KS:

As like any war I think it's wrong. I don't

believe in fighting and last time I checked war is

included. I don't know or have an answer for the war,

but I do know that killing people is not right. I

think our country is just too lazy to think of another

solution.

I:

What kinds of things are your classmates saying

about the war?

KS:

See they don't even know what they are talking

about most of the time. Most of the things they say

are just cruel about how they want to kill the whole

country. And how they are supporters of bombing. How

they should stop sending food packets out there?

I:

Now that your mother has pulled you out of school,

what kind of things are you studying at home?

KS:

History, English, Career, and Science. It's quite

funny to now know and realize how much bull crap

they're feeding you in schools

I:

What lessons have you learned from this, that you'd

like to share with teenagers in similar situations?

KS:

I've learned that this country is crap ...

actually I already knew that. I've learned that school

systems are crap. Wait! I knew that too. I guess I've

learned that this country and school systems are more

crappy than ever and they suck. I guess I've also

learned not to give up. And to stand up for what you

believe in no matter what it is. It's okay to think

differently, its normal. Don't let anyone run over you

because of your beliefs.

Katie Sierra needs support. Here are some suggested

actions:

Sissonville High School

Principal Forest Mann

The Kanawha County Board of Education

Melanie Vickers

Board of Education Site Webmaster

West Virginia ACLU

- Robert Allen

|

||

Robert Allen

Robert Allen

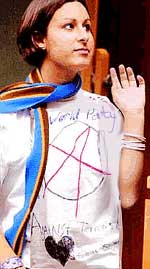

Katie Sierra, born in Panama, is a 15-year-old 10th

grader at Sissonville High School in Charleston, West

Virginia in the United States. She's become the

subject of national media attention after the high

school suspended her for anti-war sentiments and her

desire to start a student anarchist club. She was

suspended for three days in October for defying school

orders not to form an anarchy club or wear T-shirts

that include slogans opposing the U.S. bombing of

Afghanistan. The handwritten message on the T-shirt

that got her in trouble read:

Katie Sierra, born in Panama, is a 15-year-old 10th

grader at Sissonville High School in Charleston, West

Virginia in the United States. She's become the

subject of national media attention after the high

school suspended her for anti-war sentiments and her

desire to start a student anarchist club. She was

suspended for three days in October for defying school

orders not to form an anarchy club or wear T-shirts

that include slogans opposing the U.S. bombing of

Afghanistan. The handwritten message on the T-shirt

that got her in trouble read: